The steam has gone out of globalization

A new pattern of world commerce is becoming clearer—as are its costs

Jan 24th 2019

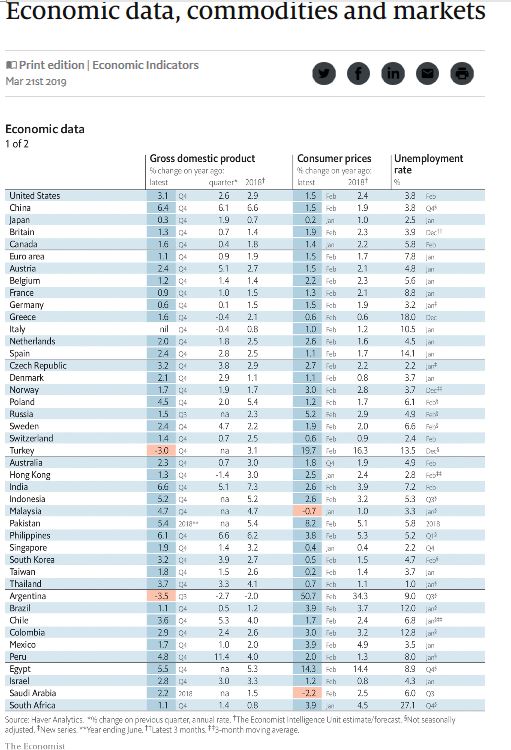

WHEN AMERICA took a protectionist turn two years ago, it provoked dark warnings about the miseries of the 1930s. Today those ominous predictions look misplaced. Yes, China is slowing. And, yes, Western firms exposed to China, such as Apple, have been clobbered. But in 2018 global growth was decent, unemployment fell and profits rose. In November President Donald Trump signed a trade pact with Mexico and Canada. If talks over the next month lead to a deal with Xi Jinping, relieved markets will conclude that the trade war is about political theatre and squeezing a few concessions from China, not detonating global commerce.

Such complacency is mistaken. Today’s trade tensions are compounding a shift that has been under way since the financial crisis in 2008-09. As we explain, cross-border investment, trade, bank loans and supply chains have all been shrinking or stagnating relative to world GDP (see Briefing). Globalization has given way to a new era of sluggishness. Adapting a term coined by a Dutch writer, we call it “slowbalisation”.

The golden age of globalization, in 1990-2010, was something to behold. Commerce soared as the cost of shifting goods in ships and planes fell, phone calls got cheaper, tariffs were cut and the financial system liberalized. International activity went gangbusters, as firms set up around the world, investors roamed and consumers shopped in supermarkets with enough choice to impress Phileas Fogg.

Globalization has slowed from light speed to a snail’s pace in the past decade for several reasons. The cost of moving goods has stopped falling. Multinational firms have found that global sprawl burns money and that local rivals often eat them alive. Activity is shifting towards services, which are harder to sell across borders: scissors can be exported in 20-ft containers, hair stylists cannot. And Chinese manufacturing has become more self-reliant, so needs to import fewer parts.

This is the fragile backdrop to Mr Trump’s trade war. Tariffs tend to get the most attention. If America ratchets up duties on China in March, as it has threatened, the average tariff rate on all American imports will rise to 3.4%, its highest for 40 years. (Most firms plan to pass the cost on to customers.) Less glaring, but just as pernicious, is that rules of commerce are being rewritten around the world. The principle that investors and firms should be treated equally regardless of their nationality is being ditched.

Evidence for this is everywhere. Geopolitical rivalry is gripping the tech industry, which accounts for about 20% of world stock markets. Rules on privacy, data and espionage are splintering. Tax systems are being bent to patriotic ends—in America to prod firms to repatriate capital, in Europe to target Silicon Valley. America and the EU have new regimes for vetting foreign investment, while China, despite its bluster, has no intention of giving foreign firms a level playing-field. America has weaponized the power it gets from running the world’s dollar-payments system, to punish foreigners such as Huawei. Even humdrum areas such as accounting and antitrust are fragmenting.

Trade is suffering as firms use up the inventories they had stocked in anticipation of higher tariffs. Expect more of this in 2019. But what really matters is firms’ long-term investment plans, as they begin to lower their exposure to countries and industries that carry high geopolitical risk or face unstable rules. There are now signs that an adjustment is beginning. Chinese investment into Europe and America fell by 73% in 2018. The global value of cross-border investment by multinational companies sank by about 20% in 2018.

The new world will work differently. Slowbalisation will lead to deeper links within regional blocs. Supply chains in North America, Europe and Asia are sourcing more from closer to home. In Asia and Europe most trade is already intra-regional, and the share has risen since 2011. Asian firms made more foreign sales within Asia than in America in 2017. As global rules decay, a fluid patchwork of regional deals and spheres of influence is asserting control over trade and investment. The European Union is stamping its authority on banking, tech and foreign investment, for example. China hopes to agree on a regional trade deal this year, even as its tech firms expand across Asia. Companies have $30 trillion of cross-border investment in the ground, some of which may need to be shifted, sold or shut.

Fortunately, this need not be a disaster for living standards. Continental-sized markets are large enough to prosper. Some 1.2 billion people have been lifted out of extreme poverty since 1990, and there is no reason to think that the proportion of paupers will rise again. Western consumers will continue to reap large net benefits from trade. In some cases, deeper integration will take place at a regional level than could have happened at a global one.

Yet slowbalisation has two big disadvantages. First, it creates new difficulties. In 1990-2010 most emerging countries were able to close some of the gap with developed ones. Now more will struggle to trade their way to riches. And there is a tension between a more regional trading pattern and a global financial system in which Wall Street and the Federal Reserve set the pulse for markets everywhere. Most countries’ interest rates will still be affected by America’s even as their trade patterns become less linked to it, leading to financial turbulence. The Fed is less likely to rescue foreigners by acting as a global lender of last resort, as it did a decade ago.

Second, slowbalisation will not fix the problems that globalization created. Automation means there will be no renaissance of blue-collar jobs in the West. Firms will hire unskilled workers in the cheapest places in each region. Climate change, migration and tax-dodging will be even harder to solve without global co-operation. And far from moderating and containing China, slowbalisation will help it secure regional hegemony yet faster.

Globalization made the world a better place for almost everyone. But too little was done to mitigate its costs. The integrated world’s neglected problems have now grown in the eyes of the public to the point where the benefits of the global order are easily forgotten. Yet the solution on offer is not really a fix at all. Slowbalisation will be meaner and less stable than its predecessor. In the end it will only feed the discontent.

For more on slowbalisation, listen to The Economist Asks, our weekly podcast.

Cause for concern? The top 10 risks to the global economy 2019

A report by The Economist Intelligence Unit

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2019

Introduction

The outlook for the global economy is worsening. Given concerns over slowing growth in key economies, including China and the EU, and the wider impact of a trade war between the US and China, The Economist Intelligence Unit expects global growth to decelerate from 2.9% in 2018 to 2.8% in 2019 and 2.6% in 2020. However, even when taking into account this downbeat assessment, there remain a number of risks emanating from three key areas that could drive growth even lower than we

currently forecast in 2019-20.

First, geopolitical uncertainty is on the rise and will remain a source of significant risk, potentially impacting trade, financial markets and the oil sector. The impact of the increase in populist and nationalist leaders in recent years has yet to become fully apparent; however, it has already contributed to growing protectionist sentiment that could escalate and widen the current US-China trade war, with a damaging effect on the global economy. On top of slowing global growth and rising geopolitical

uncertainty, there are also significant vulnerabilities in large economies—including sizeable debt burdens in China, the US and Italy, among others—and also in emerging markets, which are, in some cases, highly exposed to global trade and capital flows. If badly managed, these frailties have the potential to significantly accentuate any downturn as the global economy cools.

Lastly, a longer-term shift in global power dynamics, particularly regarding the rise of China in competition with the US, ensures that security risks continue to threaten global economic stability. Moreover, while there remain long-standing territorial disputes and conventional military threats, the security landscape continues to develop, as technological innovation adds new dimensions and more complex requirements. With various sources of risk in play, policymakers and businesses attempting to

operate in such an uncertain environment will need to devote greater resources to contingency plans,which in itself is likely to constitute a drag on global growth.

In the latest edition of this report, we offer a snapshot of our risk-quantification abilities by identifying and assessing the top ten risks to the global political and economic order. Each of the risks is outlined and rated in terms of its likelihood and its potential impact on the global economy. We also provide operational risk analysis on a country-by-country basis for 180 countries through our Risk Briefing, and detailed credit risk assessments on 131 countries via our Country Risk Service. Together,

these products enable our clients to anticipate and plan for the main threats to their organisations,supply chains and sovereign creditors. We offer robust risk modelling, scenario analysis and daily events scanning for the threats and opportunities that abound in today’s global economy.

A US-China trade conflict morphs into a full-blown global trade war

Moderate risk; Very high impact;

Risk intensity = 15

China and the US have started negotiations to resolve the current trade dispute, and the US government has decided to suspend further increases in tariffs on US$200bn-worth of Chinese goods. Talks are likely to yield a limited trade deal—involving Chinese purchases of US agricultural and energy products, but with only broad commitments to domestic economic reform, particularly over structural issues, including technology transfer and intellectual property. While this will avoid an escalation in tensions for now, a full-blown trade war between the US and China remains a significant risk to the global economy, owing mainly to the fact such a deal will lack the necessary enforcement measures to ensure Chinese commitment to the structural reforms demanded by US negotiators. Moreover, beyond bilateral protectionism, there remains a risk that trade conflicts will escalate on additional fronts in the coming years, to the extent that global trade could actually decline, with major knock-on effects for inflation, business sentiment, consumer sentiment and, ultimately, global economic growth. Currently, the most immediate risk emanates from threats by the US president, Donald Trump, to impose additional tariffs on imports of EU cars, which would result in a broader trade conflict as the EU attempts to defend its interests. However, there are further related risks. Given rising negative sentiment over national security concerns from countries such as Germany, the UK, Canada and Australia towards Chinese network providers such as Huawei, there is a risk that a number of additional countries could be dragged into a technology trade war, with international companies’ supply chains disrupted by split global network coverage. As global growth slows, this scenario could also be triggered if a number of countries were to decide to impose broad-based import tariffs and subsidize local industries in order to combat international protectionism. In either of these cases, we would expect global trade to shrink, inflation to rise, consumers’ purchasing power to fall, investment to stagnate and global economic growth to slow.

US corporate debt burden turns downturn into a recession

Moderate risk; High impact;

Risk intensity = 12

Falling consumer sentiment and manufacturing activity indicators highlight the worsening outlook for the US economy as it faces the effects of a trade war with China, the impact of a lengthy government shutdown in December-January and an eventual turn in the business cycle. Nonetheless, the economy’s fundamentals remain fairly robust, with economic growth at an estimated 2.9% in 2018, and inflation slowing to 1.9% year on year in December, despite gradually rising wage growth. In addition, the Federal Reserve (the central bank) moved to a more cautious approach to monetary policy in early 2019. Therefore, although we expect economic growth to slow to 2.3% in 2019 and to just 1.5% in 2020, our central forecast is that the US will avoid a damaging recession in 2019-20. However, along with a number of external headwinds, such as the trade war and slowing growth in Europe, domestic financial sector vulnerabilities could make the downturn much deeper than we currently expect. Fueled by a prolonged period of ultra-low interest rates, corporate debt as a percentage of GDP has surged to just under 47%, higher than the previous peak during the global financial crisis in 2008-09. In addition, the quality of this debt has fallen, with over half of US corporate debt rated BBB—the lowest investment grade—and about 60% of loans were issued without maintenance covenants in 2018. As a result, a downturn could lead to an increasing number of firms cutting investment and hiring, while also struggling to meet debt repayments, as their profits decline and as ratings agency downgrades lead investors to withdraw funding to corporations. In this scenario, a US recession would greatly exacerbate a global slowdown, with countries affected by declining US demand for goods and weakening investment.

Contagion spreads to create a broad-based emerging-markets crisis

Moderate risk; High impact;

Risk intensity = 12

Many emerging markets suffered currency volatility in 2018, primarily as a result of US monetary tightening and the strengthening US dollar. In a few instances, such as Turkey and Argentina, a combination of factors, including external imbalances, political instability and poor policy making, led to full-blown currency crises. More recently, however, the pressure on most emerging markets’ capital accounts has eased, as the US Federal Reserve has adopted a more cautious monetary policy stance. Nonetheless, market sentiment remains fragile, and pressure on emerging markets as a group could re-emerge if market risk appetite deteriorates further than we currently expect. One trigger for this could be if a number of major emerging markets were to fall into crisis, either through domestic issues and/or the impact of external pressures such as the US-China trade war. Indeed, several are already at risk, including Brazil, Mexico and South Africa. Alternatively, investors could flee emerging markets if the recent currency crises in Argentina and Turkey escalate into full-blown banking crises as the rising value of foreign-currency debt leads to defaults (although this appears unlikely). In this scenario, capital outflows from emerging markets could become more indiscriminate and severe, forcing countries with external imbalances to make painful adjustments, with the most vulnerable falling deep into crisis. Emerging-market GDP growth would fall sharply as a result, weighing on the global economy.

China suffers a disorderly and prolonged economic downturn

Low risk; Very high impact;

Risk intensity = 10

In China, a shift towards looser macroeconomic policy settings is under way as a result of the escalating trade conflict with the US. This will support domestic demand in the short term, but in the process previous goals of lowering unsold housing stock and corporate deleveraging are receiving less emphasis. There is a risk that, in the government’s efforts to support the economy, policy missteps will be made. The stock of domestic credit remained at over 230% of GDP at the end of the third quarter of 2018, a major vulnerability. Although it is likely that the authorities would make every effort to prevent a funding crunch in any bank, even a hint of banking sector distress could cause problems, given the boom in debt over recent years. Resolving these issues, particularly as the trade conflict with the US also weighs on economic activity, could prove challenging, forcing the economy into a sudden downturn. The bursting of credit bubbles elsewhere has usually been associated with a sharp deceleration in economic growth and, if this were accompanied by a house-price slump, the government might struggle to maintain control of the economy—especially if a slew of small and medium-sized Chinese banks, which are more reliant on wholesale funding, were to falter. If the Chinese government were unable to prevent a disorderly downward economic spiral, this would lead to much lower global commodity prices, particularly in metals. This, in turn, would have a detrimental effect on the Latin American, Middle Eastern and Sub-Saharan African economies that had benefited from the earlier Chinese-driven boom in commodity prices. In addition, given the growing dependence of Western manufacturers and retailers on demand in China and other emerging markets, a disorderly slump in Chinese growth would have a severe global impact—far more than would have been the case in earlier decades.

Supply shortages lead to a globally damaging oil-price spike

Low (Medium?) risk; High impact;

Risk intensity = 8

Market fears of oil-supply shortages have eased since the US granted six-month sanction waivers to eight of the key purchasers of Iranian oil in December. Along with higher output from Saudi Arabia and Russia, and global growth concerns, this has caused the price of dated Brent Blend to fall to close to US$60/barrel, compared with highs of over US$80/b in September. However, the risk of major supply disruptions remains. Should the US manage to crack down efficiently on Iran’s “ghost tankers” and also strike deals with other importers to switch their supplier bases away from Iran once the waivers have expired, Iran’s oil exports could drop well below the 1.2 million barrels/day that we currently expect in 2019-20. To combat this, Saudi Arabia and Russia have the capacity to ramp up supply, and US shale production could also fill the gap. However, as spare production capacity is used up to cover Iranian cuts, it will become more difficult to cover a sudden and sizeable cut to supply elsewhere, particularly in volatile countries such as Libya and Venezuela. As a result, prices could soar to well above the US$80/b seen in 2018, with producers unable to increase output sufficiently to put a lid on price rises. Such a scenario would push up inflation and weigh on global growth.

Territorial or sovereignty disputes in the South or East China Sea lead to an outbreak of hostilities

Low risk; High impact;

Risk intensity = 8

The national congress of the Chinese Communist Party in October 2017 was a milestone in terms of China’s overt declaration of its pursuit of great-power status, setting the goals for China to become a “leading global power” and have a “first-class” military force by 2050. The president, Xi Jinping, is keen to develop China’s global influence, probably sensing opportunity during a period of US retrenchment. How China intends to deploy its expanding hard-power capabilities in support of its territorial and maritime claims is a source of growing concern for other countries in the region. In the South China Sea the sovereignty of a number of islands and reefs is in dispute. Several members of the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) have sought to strengthen their own maritime defense capabilities amid increasingly aggressive moves by China to place military hardware on the disputed territories. A partial abdication of US leadership of global affairs could embolden China to exert its claimed historical rights in the South China Sea. Distinct possibilities include an acceleration of China’s island reclamation measures and the declaration of a no-fly zone over the disputed region. There is also a risk that an emboldened Mr Xi will step up his government’s efforts to unify Taiwan with mainland China, with the president having previously noted that the cross-Strait issue was one that could not be passed “from generation to generation”. Were military clashes to occur over any of these issues, the global economic consequences would be significant, as regional supply networks and major sea lanes could be disrupted.

Cyber-attacks and data integrity concerns cripple large parts of the internet

Moderate risk; Low impact;

Risk intensity = 6

Public, corporate and government faith in the internet as a source for global good is under strain. Revelations of major data breaches across a range of social media, and the use of that data for propaganda, are likely to see social media companies facing tighter regulation in the coming years. Meanwhile, cyber-attacks continue apace. In March 2018 the US blamed Russia for a cyber-attack on its energy grid. At a similar time there was a sustained attack on German government networks. Although these attacks have been relatively contained so far, there is a risk that their frequency and severity will increase to the extent that corporate and government networks could be brought down or manipulated for an extended period. Cyber-warfare covers a broad swathe of varying actors, both state-sponsored and criminal networks, as well as differing techniques. Recent data breaches and cyber-attacks could well be part of wider efforts by state actors to develop the ability to cripple rival governments and economies, and include efforts to either damage physical infrastructure or gain access to sensitive information as a means to influence democratic processes. These breaches of security have shaken consumer faith in the security of the internet and threaten to put at risk billions of dollars of daily transactions. Were government activities to be severely constrained by an attack or physical infrastructure damaged, the impact on economic growth would be even more severe.

There is a major military confrontation on the Korean peninsula

Very low risk; Very high impact;

Risk intensity = 5

There was a pick-up in diplomatic activity on the Korean peninsula in 2018, peaking with a historic summit in June between Mr Trump and the North Korean leader, Kim Jong-un, in Singapore. Decades of carefully planned approaches between the US and North Korea have failed, but there is a glimmer of hope that a more improvised and personal approach by two unorthodox leaders could make progress, with a second meeting between the two scheduled for late February. However, we maintain the view that there are irreconcilable differences between the US and North Korea on both the pace and the breadth of denuclearization. Although recent statements by the US Department of State have hinted at a slight easing of demands for complete, verifiable and irreversible denuclearization by 2020—the end of Mr Trump’s term—US goals nevertheless remain significantly at odds with the North’s long-term commitment to its nuclear programme. Any realistic denuclearization (which would be a step-by-step programme) would require 1020 years of sustained engagement. Such levels of bilateral trust are unlikely to be achieved under the current administration. Our core forecast is that the US will eventually be forced to revert to a containment strategy. However, should the diplomatic talks fall apart, the Trump administration could see this as justifying a more aggressive stance, including strategic strikes on the North. This option has been publicly favored by some of Mr Trump’s close advisers, such as John Bolton, the national security adviser, who was at the summit on June 12th with Mike Pompeo, the secretary of state. Under such a scenario, North Korea would almost certainly retaliate with conventional weaponry and, potentially, short-range nuclear missiles, bringing devastation to South Korea and Japan, in particular, at enormous human cost and entailing the destruction of major global supply chains.

Political gridlock leads to a disorderly no-deal Brexit

Low (medium?) risk; Low impact;

Risk intensity = 4

Although a withdrawal agreement between the EU and the UK was finalized at an EU summit on November 25th, it was initially rejected by UK members of parliament in a vote in mid-January, and only received parliamentary backing in a later vote on condition that the Irish border backstop be renegotiated. (The backstop stipulates that the UK would remain in a customs union with the EU indefinitely should a trade agreement preserving an open Irish border not be found.) However, the EU has so far rejected any reopening of withdrawal agreement negotiations. With so little room for maneuver before the March 29th deadline, we think that the UK prime minister, Theresa May, will be forced to delay Brexit by requesting an extension of the Article 50 window. The alternative would be to crash out of the EU without a withdrawal agreement and transition arrangements in place, which the government and parliament would wish to avoid. Were a no-deal Brexit to occur, we would expect this to trigger a sharp depreciation in the value of the pound and a much sharper economic slowdown in the UK than we currently forecast. In addition, the EU has indicated that under a no-deal scenario it would treat the UK as a “third country”, leading to tariffs, border checks and border controls, a stance that the UK would probably respond to in kind. Although some contingency plans have been made, the hit to UK and EU trade and investment under a disorderly no-deal scenario is likely to go beyond just the negative impact on EU economies and prove sizeable enough to dent global economic growth.

Political and financial instability lead to an Italian banking crisis

Low (medium?)risk; Low impact;

Risk intensity = 4

After growth in the preceding 14 quarters, the Italian economy contracted in both of the final quarters of 2018, constrained by a mixture of domestic political and economic uncertainty, tightening liquidity conditions and the worsening global trade outlook. In the light of this, we expect real GDP growth to slow from 0.8% in 2018 to just 0.2% in 2019. There is, however, a risk of a much deeper recession should investor confidence lead to another spike in bond yields. Triggers for this could include an early general election being called, following the possible splintering of the fragile governing coalition, or another budget stand-off (we expect weak economic growth to result in a much larger budget deficit than the stipulated 2% limit agreed with European Commission). With government debt already at over 130% of GDP, and a significant amount still held by domestic banks, this could, in turn, lead to a banking crisis, given the already-weak state of the country’s banks. As Italy is Europe’s third-largest economy, such a scenario would weigh on the region’s overall GDP growth, risk contagion to other European banks holding Italian assets and lead to volatility in global financial markets.

Canadian lumber makes inroads in Huzhou, China

By Alex Wu

Wood in Manufacturing, CW China

March 5, 2019

A Sino-Canadian timber co-operation event organized by Canada Wood China was held on January 23, 2019 in Huzhou City of eastern China’s Zhejiang Province. The goal was to help the city diversify its wood sourcing channels amid a bruising U.S.-China trade war.

Canada, as one of the world’s largest lumber producers and exporters, boasts abundant timber resources that can be used in both industrial building and manufacturing. Canadian lumber provides a big opportunity for timber companies in Huzhou as they seek new trade partners since China announced an additional 10 percent tariff on imported wood products and logs from the United States in September 2018 as a response to Washington imposing new tariffs on Chinese goods.

The matchmaking event attracted 58 people, including Katrin Spence, vice chancellor of the Consulate General of Canada in Shanghai; representatives from wood associations (including Canada Wood China and the Quebec Wood Export Bureau); Canadian wood suppliers like Interfor and Canfor, as well as wood materials and production companies in Huzhou.

The event came after Canada Wood China worked for months with its two partners, the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (CCPIT) Huzhou Committee and the Canadian Consulate General in Shanghai.

The CCPIT Huzhou signed co-operation agreements with Canada Wood China and the Quebec Wood Export Bureau during the event. The deals are designed to enhance communication and promote trade activities between companies in Huzhou city and Canada.

The majority of Huzhou’s wood imports are from North America. In the first 11 months of 2018, imported wood products from the United States were valued at around 662 million yuan (CAD$130 million), accounting for 33.5 percent of the city’s total wood imports.

Chongqing Yuanlu Community Center nabbed International Design Award

By Lance Tao

Director of Communications, Canada Wood Shanghai

March 8, 2019

Posted in: China

Chongqing Yuanlu Community Centre (Click here for gallery) designed by Jie Lee from Challenge Design, won the International Design Award on March 4. The news was announced at the 15th annual Wood Design Awards ceremony held by the organizer, WoodWORKS! BC at the Vancouver Convention Centre. A total of 10 projects from China running under this category were shortlisted in the final award.

The project, sitting next to Longxing Ancient Town in southwestern China’s Chongqing, consists of three buildings of different sizes side-by-side on the hillside. Wood is used in the Chongqing Yuanlu Community Center to closely link space and structure. Exposed Canadian Douglas fir glulam provide a crucial visual element on the interior while the order and form similar to traditional Chongqing sloping roofs are adopted for expression.

“I should say thanks to the judges and really appreciate that our project is recognized by this prestigious award. Projects in China could not accomplish this high achievement without Canadian government and Canada Wood China (CW China)’s consistency in promoting wood frame construction in China, as well as the technical support that they provide to the market, “said Jie Lee, chief designer of the Chongqing Yuanlu Community Centre (in picture), adding that they will co-operate with CW China to boost modern wood architectures in China.

China makes up two-thirds of award nominees in the International Wood Design category this year. These nominees feature in the resort and public service sectors. Seven of the projects are in eastern China, including two in Shanghai. The remaining three projects are in central and southwestern China.

In total, 103 projects in 14 categories (including designs, environmental performances, western red cedar, wood innovation, engineer, and architecture) were nominated this year. Submissions are from the United States, China, South Korea and Tajikistan, in addition to British Columbia.

A diversity of projects of various types and sizes demonstrating outstanding architectural and structural achievement using wood are among the nominees. They include a research laboratory, an energy facility, a winery, First Nations structures and mid-rise projects, according to the award’s press release.

To celebrate wood design projects at home and abroad, the Wood Design Awards are presented by Wood WORKS! BC, the Canadian Wood Council and its member associations; with funding support from Natural Resources Canada and Forestry Innovation Investment.

Click here to learn more about the 10 China Nominee Projects for the 2019 Wood Design Awards.

‘PRIMO VILLAGE’, Rental House Exclusively for U.S. Army Civilians

By Sunny Kim

Program Manager / Market Development & Market Access, Canada Wood Korea

January 3, 2019

Posted in: Korea

As the transfer of the U.S. military facilities in Yongsan Seoul to Pyeongtaek Gyeonggi-do is picking up speed, the housing market for U.S. army civilians is heating up. In the market, the ‘PRIMO VILLAGE – Rental House Exclusively for U.S. Army Civilians’, a village with 45 housing units developed by Gahee Development in Eumbong-myeon, Asan-si, is drawing attention.

PRIMO VILLAGE, In-cheol Jeong, the president of Gahee Development said, “These are rental houses for U.S. army civilians and designs specifically for American housing culture is most important. PRIMO VILLAGE, was designed in the US and constructed with the best materials imported from North America and Germany.”

One of the major materials used is ICYNENE foam, an insulation material imported from Canada that is increasing in popularity in Korea.

For latest Canada Wood market summaries in Asia see this link https://gallery.mailchimp.com/3d038d81cf674d563452ee221/files/79a18e78-4783-4096-8913-f51dd544ff50/CanadaWood_FII_Market_Summary_Report_Interim_2_2018_19_FINAL.pdf

Rising borrowing costs, increased government regulation and volatile stock markets playing a role, along with dwindling demand from Chinese buyers

BLOOMBERG NEWS

Updated: January 4, 2019

Asia is finally succumbing to the global property slowdown that’s jolted homeowners and investors from Vancouver to London, with markets in Singapore, Hong Kong and Australia showing fresh signs of softening.

The economic ramifications could be serious. Lower house prices and higher mortgage rates will not only dent consumer confidence, but also disposable incomes, S&P Global Ratings said in a report last month. A simultaneous decline in house prices globally could lead to “financial and macroeconomic instability,” the IMF said in study released in April.

While each city in the region has its own distinct characteristics, there are a few common denominators: rising borrowing costs, increased government regulation and volatile stock markets. There’s also dwindling demand from a force so powerful it pushed prices to a record in many places — Chinese buyers.

- The year higher borrowing costs and stricter mortgage rules hit home

- Vancouver home sales fall to lowest yearly total in 18 years, detached home prices drop

- When this man talks about housing markets, people listen — and now he’s deeply concerned

“As China’s economy is affected by the trade war, capital outflows have become more difficult, thus weakening demand in markets including Sydney and Hong Kong,” said Patrick Wong, a real estate analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence.

Hong Kong

After an almost 15-year bull run that made Hong Kong notorious for having the world’s least affordable property market, home prices have taken a battering.

Values in the city have fallen for 13 weeks straight since August, the longest losing streak since 2008, figures from Centaline Property Agency Ltd. show. Concerns about higher borrowing costs and a looming vacancy tax have contributed to the slide.

buildings stand illuminated in Hong Kong, China. PAUL YEUNG/BLOOMBERG

The strike rate of mainland Chinese developers successfully bidding for residential sites is also waning, tumbling to 27 per cent in 2018 from 70 per cent in 2017, JLL’s Residential Sales Market Monitor released Thursday showed. Of the 11 residential sites tendered by authorities last year, only three were won by Chinese companies.

“The change in attitude can be explained by a slowing mainland economy,” said Henry Mok, JLL’s senior director of capital markets. “Throw in a simmering trade war between China and the U.S., the government has taken actions to restrict capital outflows, which in turn has increased difficulties for developers to invest overseas.”

Singapore

Home prices on the island, which regularly ranks among the world’s most expensive places to live, posted their first drop in six quarters in the three months ended December. Luxury was hit the hardest, with values in prime areas sinking 1.5 per cent.

Government policies are mainly to blame. Cooling measures implemented unexpectedly in July included higher stamp duties and tougher loan-to-value rules. Extra constraints since then have included curbs on the number of “shoe-box” apartments and anti-money laundering rules that imposed an additional administrative burden on developers.

It’s all worked to put the brakes on a home-price recovery that only lasted for five quarters, the shortest since data became available.

“Landed home prices, being bigger ticket items, have taken a greater beating as demand softened,” said Ong Teck Hui, a senior director of research and consultancy at JLL. (In Singapore, most people live in high-rise apartments, called housing development board flats. Landed homes by contrast occupy their own ground space.)

Sydney

Sydney-siders have begun to wonder — what sort of economic fallout will there be from the wealth destruction that comes with the worst slump in home values since the late 1980s?

Average home values in the harbor city have fallen 11.1 per cent since their 2017 peak, according to CoreLogic Inc. data released Wednesday — surpassing the 9.6 per cent top-to-bottom decline when Australia was on the cusp of entering its last recession.

While prices are still about 60 per cent higher than they were in 2012, meaning few existing homeowners are actually underwater, it’s economist forecasts of a further 10 per cent fall that’s making nervous investors think twice about extraneous spending.

The central bank is also worried that a prolonged downturn will drag on consumption and with the main opposition Labor party pledging to curb tax perks for property investors if it wins an election expected in May, confidence is likely to be hit further.

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg on Thursday urged the nation’s banks not to tighten credit any more as the deepening downturn threatens to weigh on the economy.

Shanghai, Beijing

A crackdown on overheating prices has hampered sales and left values in the nation’s biggest cities around 5 per cent below their peak. Rules on multiple home purchases, or how soon a property can be sold once it’s bought, are starting to be relaxed, and there are giveaways galore as home builders try to lure buyers.

One developer in September was giving away a BMW Series 3 or X1 to anyone wishing to purchase a three-bedroom unit or townhouse at its project in Shanghai. Down-payments have also been slashed, with China Evergrande Group asking for just 5 per cent compared with the usual 30 per cent deposit required.

“It’s not a surprise to see Beijing and Shanghai residential prices fall given the curbing policies currently on these two markets,” said Henry Chin, head of research at CBRE Group Inc. An index that measures second-hand home prices in Beijing has been falling since September while one that tracks Shanghai has been on the decline now for almost 12 months, he said.

Mar 13, 2019 | 11:00 GMT

7 mins read

China Opts for Tax Cuts to Jolt Its Economy Awake

(KEVIN FRAYER/Getty Images)

Highlights

- With its economy slowing, China will rely more on fiscal policies — including tax relief — to re balance its economy to bolster private consumption and investment.

- However, tax relief, coupled with the overall slowdown, will result in tighter budgets for local and central governments, particularly in the central and western regions.

- Beijing will issue more local bonds, increase fiscal transfers and expand the local tax base with new property tax reforms to ease local governments’ financial burden.

Spurred in part by its slowing economy, China is gathering steam in its efforts to re balance its tax structure. During the country’s annual legislative session this month, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang announced an expanded 2 trillion-yuan ($298 billion) reduction — or 10 percent of China’s total government budget revenues last year — in taxes and fees for individual taxpayers and private business this year. Together with a smaller package last year, the measures could free 100 million individual taxpayers (mainly lower- and middle-class citizens) from income tax and lower the tax burden for private enterprises by as much as 20 percent. The tax package is designed to ease the growing financial stress on private businesses and kick-start flagging consumption amid the Chinese economy’s struggles with high debt and the lack of impact from traditional government-led investments.

The Big Picture

In the decade since the global financial crisis, Beijing has relied on expanded credit to develop infrastructure and the property market to ameliorate economic pain amid a slow-moving economic transition. But as China faces multiple challenges, including an extended economic slowdown, the U.S. trade war and diminishing returns from its previous stimulation policies, Beijing is turning more toward different fiscal policies to address economic challenges.

See 2019 Second-Quarter Forecast

See Asia-Pacific section of the 2019 Second-Quarter Forecast

Although the central government is on a relatively sound financial footing, growing imbalances (overall revenue sources are slowing — or even declining — while expenditures are growing) mean local governments will bear the brunt of the expected shortfall, since many are already wallowing in high debt. In response, Beijing will use various methods, including fiscal transfers, more bond issuance and the cultivation of new tax bases, to plug the gap; yet these measures have their drawbacks, ensuring that China’s continued economic slowdown will limit just how far Beijing can go in righting the ship.

Providing Tax Relief

Beijing’s resort to tax cuts speaks volumes about China’s present reality. But following a decade long credit boom, the majority of which flowed into government-led infrastructure projects and property investments, the costs of the expansion are now outweighing the benefits. Beyond high debts and excessive industrial capacity in state-owned sectors, as well as over speculation in the property market, policies that funneled capital into state-owned enterprises instead of the private sector — the focus of most production and innovation — hurt the latter. At the same time, China is finding itself in a tight squeeze as it tries to incentivize domestic spending (a critical aspect of Beijing’s attempts to re balance) due in part to rising mortgage and overall household debt, which have grown the last three years. Essentially, now that quick-fix solutions are no longer as effective as before, China’s leaders have no choice but to resort to less-palatable measures to put the country back on track to sustainable growth.

Still, tax cuts for corporations and households alone are unlikely to deliver the same effects as credit expansions or state-led investment spending. Although the relief will certainly help alleviate the burdens for companies and individuals, its net impact will be relatively light since the extended economic slowdown will deter consumption and private investments at a time when many small- to medium-sized private corporations are struggling to make ends meet. Last year, for example, overall industrial profits contracted for several key manufacturers in the information technology, automotive and other sectors, even though the government offered 1.3 trillion yuan in tax relief. Likewise, this year’s tax package, which amounts to roughly 2 percent of gross domestic product, is only expected to generate 0.5 percent in GDP growth. In other words, if China’s tax strategy is to succeed, Beijing must complement its supplementary policies with a more sustainable approach to support the real economy so consumers can spend and companies can expand their business scale and capital expenditures.

Tightening the Belt

Given the limited impact of the tax cut, the government will have to continue pumping money into infrastructure and investments and pursue other monetary policies to stimulate the economy. The challenge for China, however, is that it must do so against the backdrop of slowing, and perhaps even declining, overall revenue sources. Central government revenues have already slowed for two years straight, even dipping into the negative a few times in the final months of 2018 as a result of the decelerating economy and the tax cut.

Provincial and regional governments, meanwhile, are likely to come under greater stress. Significantly, land sales, which accounted for roughly half of local governments’ total revenue sources in 2017, slowed sharply in 2018 because of continued restrictions on the property market. Partly as a result of these limitations, nearly half of China’s provinces reported slower growth in local fiscal revenues last year. (Tianjin, meanwhile, even reported falling revenue.) And unless the government takes action to boost the real estate market in the coming months by loosening restrictions preventing homeowners from buying additional property or engaging in speculation, continued economic stress will likely further weaken provincial governments’ fiscal position, just as tax cuts are taking effect and other expenditures are growing.

Ultimately, the growing fiscal stress has compelled both the central and local governments to tighten the belt this year. At present, China has forecast a budget deficit of 2.8 percent of GDP for 2019 — a figure that is far below that of many other major countries like the United States (3.9 percent) and Japan (3.7 percent) — but the final number is likely to be much higher. In the recent legislative session, nearly all provincial and regional governments reduced their projections for revenue growth this year, with several provincial governments, even those in wealthy coastal regions, looking to tighten bureaucratic expenditures by as much as 5 percent this year. In less prosperous regions, including Guizhou in the southwest or Inner Mongolia in the north, the target for cuts is as high as 10 percent. And with many provinces and regions already facing debt stress (especially those in the central and west with weaker financial abilities), fiscal constraints will add further challenges, undermining their ability to maintain economic and, by extension, social stability.

Coping With the Stress

To address the problem, Beijing has increased this year’s local government bonds by 3.08 trillion yuan, a 41 percent rise year on year. Officially, local government debts remained at a healthy level of 18.4 trillion yuan, or 20 percent of GDP, at the end of 2018, but the true figure is estimated to be as much as 40 trillion yuan. In the end, with the fiscal stress unlikely to abate in the next two years, the local bonds essentially presage a greater local debt burden.

The current tax structure, which is based on a 1994 tax reform, has widened the fiscal imbalance between the central and local governments, privileging the former. But because local governments must foot the bill for the tax reduction and the growing fiscal burden, these jurisdictions will have greater cause to demand that Beijing increase fiscal transfers — even though such payments could erode the central government’s financial strength in the long term. In 2017, 80 percent of the central government’s revenue found its way to local governments, accounting for roughly 40 percent of local jurisdictions’ total expenditures. Among the country’s 31 provinces, just a handful of them — primarily eastern or coastal regions such as Beijing, Shanghai and Guangdong — are close to fiscal self-sufficiency, thereby allowing them to contribute to the central government’s coffers. But as tax bases in these wealthy regions begin to evaporate, the growing outflow in financial transfers could also create disagreements between Beijing and these wealthy regions, as well as among local governments themselves.

Beijing, meanwhile, has been attempting to cultivate new tax bases by increasing dividends from state-owned companies, exercising tighter fiscal enforcement and finding new sources of tax, especially the long-discussed property tax. While the efforts to find new tax bases could raise the ire of the state-owned companies, the property tax could further hit the moribund property sector and, thus, the economy at large. With its economy facing strong headwinds, China will struggle to implement the necessary measures, leaving it on course for a more precarious position down the road.

Putin’s Russia Embraces a Eurasian Identity

Senior Eurasia Analyst, Stratfor

(Shutterstock)

Highlights

- In the years to come, demographic change will further distinguish Russia from the West culturally and politically and more strongly emphasize its unique Eurasian identity.

- Russia’s prolonged standoff with the West will spur Moscow to develop closer economic and security ties with countries in the eastern theater, particularly in the Asia-Pacific and the Middle East, as Moscow seeks a greater balance in its relations between East and West.

- In the long term, China’s rise will temper Russia’s shift to the East and could bring about an eventual rapprochement with the West, with Moscow’s maneuvering between the Western and Eastern poles serving to shape the Eurasian aspect of Russia’s identity.

In a New Year’s message to U.S. President Donald Trump, Russian President Vladimir Putin wrote that Russia was “open to dialogue with the United States on the most extensive agenda.” The message was a hopeful one for 2019, written to close out a year in which relations between Russia and the West continued to deteriorate along numerous fronts. Russia’s standoff with the West will likely only intensify this year. A key evolution in Russia’s strategy — indeed, in Russia’s very identity — over the course of the Putin era is a big reason why.

The Big Picture

Since Vladimir Putin came to power nearly 20 years ago, Russia has developed a Eurasian identity and strategy that has made it increasingly distinct from the West. Looming demographic changes and Russia’s foreign policy maneuvering between the West and China will only solidify its Eurasian identity in the years to come.

See Russia’s Internal StruggleSee The Fight for Russia’s BorderlandsSee Moscow Looks to the East

From the Cold War to ‘Eurasianism’

To understand this evolution, it is important to understand the context in which Putin came to power nearly 20 years ago. When he was appointed acting Russian president on Dec. 31, 1999, his country was reeling from a decade of chaos and instability following the collapse of the Soviet Union. The economy was in shambles, the political system had fragmented, a separatist conflict raged in Chechnya, and oligarchs in many ways had become more powerful than the state. Even the country’s very territorial integrity was at stake.

Over the next decade, Putin reined in the oligarchs and re-established a strongly centralized state. He squashed the Chechen conflict with a combination of brute military force and political maneuvering. And the economy, with the help of strong energy prices, surged. Putin’s consolidation of power on the domestic front enabled Russia to reassert itself across the former Soviet periphery and beyond.

Russia’s resurgence as a regional power brought it into greater confrontation with the West, as Moscow sought to stop and reverse the spread of European Union and NATO membership and Western influence into the European borderlands and re-establish its own influence and integration efforts. These dynamics were seen in the Russia-Georgia War in 2008 and intensified with the Euromaidan uprising in Ukraine in 2014. The result has been a prolonged and growing standoff between Russia and the West, with its involvement in the conflicts in Ukraine and Syria, plus military buildups and Western sanctions bringing Moscow’s relations with Europe and the United States to their lowest point since the Cold War.

In the two decades since Putin ascended to the presidency, a distinct Russian identity emerged under him, one that can be called “Eurasianism.” This identity includes components of a political ideology and a foreign policy strategy that are rooted in Russia’s position in both Europe and Asia, and in geopolitical imperatives that long predate Putin. It’s an identity key both to understanding Russia’s policies now, and forecasting what can be expected in the years to come.

Eurasianism as a Political Ideology

An important political attribute of Eurasianism in the Putin era — one in line with Russian tradition — is the pursuit of collective stability over individual liberty. For most Russians, the country’s chaotic experiment with democracy and capitalism in the 1990s proved that Western-style structures were not appropriate or effective within Russia. The political culture that has arisen under Putin is incompatible in many ways with the liberal, democratic values of the West. Indeed, Moscow sees support by the United States and the European Union for pro-democracy and human rights movements inside Russia as subversive attempts to weaken it.

Russia is run as a centralized state, with Putin representing himself as a strong, decisive leader who holds together a country that otherwise would splinter apart. While the Kremlin frequently cracks down on protests and independent media, it does allow selective demonstrations and at times will even concede to certain demands — such as allowing direct elections or adjusting unpopular pension reforms — if it comes under enough pressure.

Under Putin, Russian nationalism has replaced the universal Communist ideology of the Soviet Union. However, because he must incorporate the country’s more than 150 ethnic minorities — Tatars, Chechens, Ukrainians, Armenians and so on — into this nationalism as well as its ethnic Russians, Putin manages Russia’s nationalist tendencies carefully. Orthodox Slavs are not the only face of Russia, and Putin risks alienating the country’s minority groups and undermining the stability he has worked to reinstate if he pursues a nationalist line too strongly. The same is true for religion: Muslims in Russia number in the millions, and many are concentrated in the volatile North Caucasus region.

Russia’s minority populations also are growing, while the ethnic Russian population is decreasing. Ethnic Russians made up about 77 percent of Russia’s population, according to the last official census taken in 2010, but their low birthrates (1.3 children per woman, on average) means the ethnic Russian population will decline at a faster rate than Russia’s Muslim population, which has a birthrate of 2.3 children per woman. Increased migration from the Caucasus and Central Asian states, which are also growing in population, will be necessary to meet Russia’s labor needs and will swing the country’s demographics even further. Russia will become less Slavic and Orthodox and more Asian and Muslim in the coming years, further distinguishing it culturally and politically from Europe and the West. The need to promote Russian nationalism — the greatness of Russia itself, not ethnic Russians — will only intensify.

Eurasianism as a Foreign Policy Strategy

Because Russia lacks significant natural barriers, a constant throughout its history has been the need to maintain a regional power to establish buffer space both in the east and west to protect its Moscow-St. Petersburg core. Thus, Moscow wants to keep the former Soviet republics in its fold — not necessarily officially, but certainly in a de facto manner.

It is no coincidence that the countries most closely aligned with Russia are members of the Eurasian Economic Union and its military counterpart, the Collective Security Treaty Organization, the two primary integration blocs created in the Putin era. These states share numerous features with Russia in terms of their Eurasian character — strong leaders, state-dominated economies and an emphasis on stability over democracy. They also share strong suspicions of the West and its promotion of democracy and human rights.

Ideally for Russia, every state in the former Soviet Union would be part of the Eurasian union. But states like Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan have chosen to remain neutral, while other states, including the Baltic countries and more recently Ukraine, have sought a pro-Western path. Russia’s goal is to align each of the countries in the former Soviet periphery with Moscow or at least keep them neutral. If not, Russia will aim to undermine their pro-Western governments and their Western integration efforts. The intent of the United States and its EU and NATO allies to deprive Russia of this sphere of influence is a key factor behind Moscow’s enduring standoff with the West

Eurasianism as a foreign policy concept is not limited to the lands immediately surrounding Russia. It extends to those countries that also behave in contradiction to Western liberal values and/or Western interventionism, and can include European countries that have illiberal tendencies. One example is Hungary, whose government Russia works to support in order to undermine EU unity on issues such as sanctions against it. The common thread is that Russia seeks to cooperate with countries challenging the U.S.-led world order, or at least stoke division within U.S.-allied blocs like NATO and the European Union.

Under Putin, Moscow has worked to build other economic and security relationships, not only to replace or supplement its weakened ties with the West, but also to enhance its global position as a counterweight to the West, and especially to the United States. One such place has been Syria. Russia’s intervention on behalf of Syrian President Bashar al Assad is motivated by its historical ties to the country, including maintaining a naval base at Tartus, and a strategic interest to combat the spread of the Islamic State. But just as importantly, Russia wanted to draw a red line around efforts by the West, and by the United States in particular, to force regime change in Syria. Russia’s intervention was not to save al Assad per se, but rather to serve notice to the United States that it still carried enough military and diplomatic heft to hold its own in the conflict.

This, in turn, allowed Russia to expand its influence elsewhere in the Middle East. With its economic ties with the United States and the European Union on the downswing, Russia was interested in expanding its arms sales, with Middle Eastern countries like Egypt and Turkey representing promising markets. Russia also wanted to expand its leverage against the United States in a crucial theater to Washington.

Perhaps the most important partner to emerge for Russia in the wake of Moscow’s standoff with the West is China. Russia and China had been steadily tightening their economic and energy ties since the early post-Soviet period. However, the Euromaidan uprising and Russia’s ensuing standoff with the West accelerated the development of the Moscow-Beijing relationship, not only in terms of trade and investment but also on security and military aspects. Russia and China have also coordinated their efforts on political matters when it comes to U.N. Security Council votes on issues like North Korea and Syria, particularly when it means opposing the U.S. position in these theaters.

However, Russia’s shift toward China is unlikely to last forever. China’s own rise and overlapping spheres of influence in Central Asia, the Russian Far East and the Arctic ultimately will limit the extent of their partnership. This could pave the way for a future rapprochement between Russia and the West, particularly as China emerges as a more serious economic and military competitor for both the United States and Russia down the line.

Ultimately, Russia’s maneuvering between West and East will further solidify the Eurasian aspect of its identity. The cohesion of the Russian state and society on the home front and Russia’s ability to overcome external challenges and pressures, whether from the West or China, will serve as key factors shaping the evolution of this identity.

Economist Intelligence Unit

The findings of the latest Worldwide Cost of Living Survey

Cost convergence across continents

For the first time in the survey’s history, three cities share the title of the world’s most expensive city: Singapore, Hong Kong and France’s capital, Paris. The top ten is largely split between Asia and Europe, with Singapore representing the only city in the top ten that has maintained its ranking from the previous year. In the rest of Asia, Osaka in Japan and Seoul in South Korea join Singapore and Hong Kong in the top ten. The Japanese city has moved up six places since last year, and now shares fifth place with Geneva in Switzerland. In Europe, the usual suspects—Geneva and Zurich, both in Switzerland, as well as Copenhagen in Denmark—join Paris as the world’s most expensive cities to visit and live in out of the 133 cities surveyed.

Within western Europe it is non-euro area cities that largely remain the most expensive. Zurich (in fourth place), Geneva (joint fifth) and Copenhagen (joint seventh) are among the ten priciest. The lone exception is Paris (joint first), which has featured among the top ten most expensive cities since 2003. With west European cities returning to the fold, the region now accounts for three of the five most expensive cities and for four of the top ten. Asia accounts for a further four cities, while Tel Aviv is the sole Middle Eastern representative.

Across geographic regions and countries, the survey observed a degree of convergence in 2018 among the most expensive locations. Some of those economies with appreciating currencies, like the US, climbed up the ranking significantly. In seventh and joint tenth place respectively, New York and Los Angeles are the only cities in the top 10 from North America. A stronger US dollar last year has meant that cities in the US generally became more expensive globally, especially relative to last year’s ranking. New York has moved up six places in the ranking this year, while Los Angeles has moved up four spots. These movements represent a sharp increase in the relative cost of living compared with five years ago, when New York and Los Angeles tied in 39th position.

Tel Aviv, which was ranked 28th just five years ago, sits alongside Los Angeles as the joint tenth most expensive city in the survey. Currency appreciation played a part in this rise, but Tel Aviv also has some specific costs that drive up prices, notably those of buying, insuring and maintaining a car, all of which push transport costs 64% above New York prices.

Last year inflation and devaluations were prominent factors in determining the cost of living, with many cities tumbling down the ranking owing to economic turmoil, currency weakness or falling local prices. Places like Argentina, Brazil, Turkey and Venezuela experienced all of the aforementioned conditions, leading to cities in these countries seeing a sharp fall in their cost of living ranking. Unsurprisingly, it is Caracas in Venezuela which claims the title of the least expensive city in the world. Following inflation nearing 1,000,000% last year and the Venezuelan government launching a new currency, the situation continues to change almost daily. The new currency value has varied so much since its creation and the economy was demonetized compelling people to use commodities and exchange services and personal items like clothing, auto parts and jewelry to purchase basic goods such as groceries.© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2019 2

The impact of high inflation and currency denominations is reflected in the average cost of living this year. Taking an average of the indices for all cities surveyed using New York as the base city, the global cost of living has fallen to 69%, down from 73% last year. This remains significantly lower than five years ago, when the average cost of living index across the cities surveyed was 82% and ten years ago was 89%.

US cities rise up to meet European veterans

Much of 2018 was marked by continued strong US economic growth and steady monetary policy tightening by the Federal Reserve (the US central bank), which led to a sharp appreciation of the US dollar. With the dollar strengthening against other currencies, all but two US cities rose up the ranking in 2018. The highest climbers were San Francisco (25th up from 37th previously), Houston (30th from 41st), Seattle (38th from 46th) and Detroit and Cleveland (joint 67th from joint 75th). New York (seventh), Los Angeles (tenth) and Minneapolis (20th) are all ranked in the top 20. Domestic help and utilities remain expensive in North America, with US cities ranking highly in these categories.

On the other side of the Atlantic, despite the euro making gains against the US dollar in 2017, these gains went into reverse in 2018 as economic momentum slowed and the election of a populist coalition in Italy raised new concerns about challenges to European integration. Paris stands out as the only euro area city in the top ten. The French capital, which has risen from seventh position two years ago to joint first, remains extremely expensive to live in, with only alcohol, transport and tobacco offering value for money compared with other European cities. Copenhagen in Denmark, which pegs its currency to the euro, also features in the ten priciest cities in joint seventh place, largely owing to relatively high transport, recreation and personal care costs.

When looking at the most expensive cities by category, Asian cities tend to be the priciest locations for general grocery shopping. European cities tend to have the highest costs in the household, personal care, recreation and entertainment categories—with Zurich and Geneva the most expensive in these categories—perhaps reflecting a greater premium on discretionary spending.

The impact of high inflation and currency denominations is reflected in the average cost of living this year. Taking an average of the indices for all cities surveyed using New York as the base city, the global cost of living has fallen to 69%, down from 73% last year. This remains significantly lower than five years ago, when the average cost of living index across the cities surveyed was 82% and ten years ago was 89%.

US cities rise up to meet European veterans

Much of 2018 was marked by continued strong US economic growth and steady monetary policy tightening by the Federal Reserve (the US central bank), which led to a sharp appreciation of the US dollar. With the dollar strengthening against other currencies, all but two US cities rose up the

ranking in 2018. The highest climbers were San Francisco (25th up from 37th previously), Houston (30th from 41st), Seattle (38th from 46th) and Detroit and Cleveland (joint 67th from joint 75th). New York (seventh), Los Angeles (tenth) and Minneapolis (20th) are all ranked in the top 20. Domestic help and utilities remain expensive in North America, with US cities ranking highly in these categories.

On the other side of the Atlantic, despite the euro making gains against the US dollar in 2017, these gains went into reverse in 2018 as economic momentum slowed and the election of a populist coalition in Italy raised new concerns about challenges to European integration. Paris stands out as the only euro area city in the top ten. The French capital, which has risen from seventh position two years ago to joint first, remains extremely expensive to live in, with only alcohol, transport and tobacco offering value

for money compared with other European cities. Copenhagen in Denmark, which pegs its currency

to the euro, also features in the ten priciest cities in joint seventh place, largely owing to relatively high transport, recreation and personal care costs.

When looking at the most expensive cities by category, Asian cities tend to be the priciest locations for general grocery shopping. European cities tend to have the highest costs in the household, personal care, recreation and entertainment categories—with Zurich and Geneva the most expensive in these categories—perhaps reflecting a greater premium on discretionary spending.

A year of currency fluctuations and inflation

Currency fluctuations continue to be a major cause for changes in the ranking. In the past year a number of markets have seen significant currency movements, which have in many cases countered the impact of domestic price changes.

Several emerging markets suffered currency volatility, primarily as a result of monetary tightening in the US and the strengthening US dollar. In a few instances, however, such as Turkey and Argentina, a combination of factors, including external imbalances, political instability and poor policymaking, led to full-blown currency crises. Istanbul, in Turkey, which experienced the sharpest decline in the cost of living ranking in the past 12 months, fell by 48 places to joint 120th. The reason for this drastic decline was the recent sharp slide of the Turkish lira and annual consumer price inflation surging to 25.2% in October 2018.

The impact of currency devaluation was also felt in Argentina’s capital, Buenos Aires, which has joined the bottom ten in joint 125th place. Like Istanbul, the city also fell by 48 places in the ranking following a crisis of confidence in Argentina, resulting in the peso weakening sharply against the US dollar in August.

In contrast, the endemic high cost of living in the French territory of New Caledonia partly reflects a lack of competition, particularly in the wholesale and retail sectors, which are dominated by a small number of companies. These factors drove its capital, Nouméa, 33 spots up the ranks in joint 20th place.

Another big mover, Sofia (currently joint 90th) in Bulgaria, reflects a rise up the rankings of 29 spots.

Bulgaria is an economically stable east European country, which pegs its currency, the Bulgarian lev, to the euro but is yet to join the euro zone. Like many cities in the region, Sofia continues to offer good value for money. Nevertheless, prices for groceries in the capital city are beginning to converge with west European destinations in anticipation of the country adopting the euro currency in the coming years. Growth in food prices (one of the main drivers of 3% inflation in the country for 2018) averaged 2.6% year on year in December 2018. Utility prices (electricity, gas, district heating and water) as well as recreation and culture prices, continued to rise at the slightly higher pace of around 4% over the last 12 months.

Changes at the bottom

The cheapest cities in the world have seen some changes over the past 12 months. Asia is home to some of the world’s most expensive cities, but also to many of the world’s cheapest cities. Within Asia, the best value for money has traditionally been offered by South Asian cities, particularly those in India and Pakistan. To an extent this remains true, and Bangalore, Chennai, New Delhi and Karachi feature among the ten cheapest locations surveyed. India is tipped for rapid economic expansion but, in per- head terms, wage and spending growth will remain low. Income inequality means that low wages are the norm, limiting household spending and creating many tiers of pricing as well as strong competition from a range of retail sources. This, combined with a cheap and plentiful supply of goods into cities from rural producers with short supply chains as well as government subsidies on some products, has kept prices down, especially by Western standards.

Nonetheless, although South Asian cities traditionally occupy positions among the ten cheapest, they are no longer the cheapest in the world. Last year that title was held by Syria’s capital, Damascus, which is ranked second-cheapest this year. The citizens of Damascus might not have felt that the city was getting cheaper, however, with inflation averaging an estimated 28% in the country during 2017. Yet local price rises have not completely offset a near-consistent decline in the value of the Syrian pound since the onset of war in 2011.

This year, Damascus bestowed the title of least expensive city in the world to Venezuela’s capital, Caracas, which saw a significant worsening of economic conditions in 2018, with hyperinflation and a breakdown in public services fueling growing social unrest. The Venezuelan government unified and devalued the official exchange rates in early 2018 in an attempt to reduce currency pressure, but amid hyperinflation, the currency remains hugely overvalued, as reflected in an extremely large black- market premium.

Cheap but not always cheerful

As Damascus and Caracas show, a growing number of locations are becoming cheaper because of the impact of political or economic disruption. Although South Asia remains structurally cheap,

political instability is becoming an increasingly prominent factor in lowering the relative cost of living. This means that there is a considerable element of risk in some of the world’s cheapest cities. Karachi in Pakistan, Tashkent in Uzbekistan, Almaty in Kazakhstan and Lagos in Nigeria have faced well- documented economic, political, security and infrastructural challenges, and there is some correlation between The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Worldwide Cost of Living ranking and its sister ranking, the Global Livability survey. Put simply, cheaper cities also tend to be less livable.

A bumpy ride ahead

The cost of living is always fluctuating, and there are already indications of further changes that are set to take place during the coming year. After an encouraging albeit slower 2018, The Economist Intelligence Unit expects 2019 to proceed along similar lines, with global growth slowing further this year and reaching its nadir in 2020. External conditions deteriorated late last year owing to the US- China trade war and externalities related to this are expected to continue throughout 2019.

The strong US dollar observed last year is also not set to last. Since December the dollar has softened and is expected to depreciate further against the euro and the yen from late 2019 onward as the US economy slows more sharply.

After five consecutive years of decline, oil prices bottomed out in 2016 and rebounded in 2017 and 2018, along with other commodity prices. At the very basic level, this will have an impact on prices, especially in markets where basic goods make up the bulk of the shopping basket. But there are further implications. Oil prices will continue to weigh on economies that rely heavily on oil revenue. This could mean austerity, economic controls and weak inflation persisting in affected countries, depressing consumer sentiment and growth.

Equally, 2019 could see the fallout from several political and economic shocks having a deeper effect. The UK has already seen sharp declines in the relative cost of living owing to the Brexit

referendum and related currency weaknesses. In 2019 these are expected to translate into further price rises as supply chains become more complicated and import costs rise. These inflationary effects could be compounded if sterling were to stage a recovery.

There are other unknowns as well. The US president, Donald Trump, has caused some significant upheaval in trade agreements and international relations, which may push up prices for imports and exports around the world as treaties unravel or come under scrutiny. Meanwhile, measures adopted in China to address growing levels of private debt are still expected to prompt a slowdown in consumption and growth over the next two years. This could have consequences for the rest of the world, resulting in further staged renminbi devaluations that would affect the relative cost of living in Chinese cities. The lasting impact of the US-China trade war is still to be judged, but there are already signs of the weaker global economic environment, which is only set to deepen.

Instability and conflict around the world could continue to fuel localised, shortage-driven inflation, which would have an impact on the cost of living in certain cities. Caracas, currently sitting at the bottom of the ranking, has moved down the index significantly in recent years. Equally, exchange- rate volatility has meant that, while Asian cities have largely risen in cost-of-living terms, many urban centres in China, South Africa and Australia have seen contrasting movements from year to year. It is also worth remembering that local inflation driven by instability is often counteracted by economic weakness and slumping exchange rates. As a result, cities that have the highest inflation will often see their cost of living fall compared with that of their global peers.

With emerging economies supplying much of the wage and demand growth, it seems likely that these locations will become relatively more expensive as economic growth and commodity prices recover. However, price convergence of this kind is very much a long-term trend, and in the short and medium term the capacity for economic shocks and currency swings can make a location very expensive or very cheap very quickly.

Background: about the survey

The Worldwide Cost of Living is a biannual Economist Intelligence Unit survey that compares more than 400 individual prices across 160 products and services. These include food, drink, clothing, household supplies and personal care items, home rents, transport, utility bills, private schools, domestic help and recreational costs.

The survey itself is a purpose-built Internet tool designed to help human resources and finance managers calculate cost-of-living allowances and build compensation packages for expatriates and business travellers. The survey incorporates easy-to-understand comparative cost-of-living indices between cities. The survey allows for city-to-city comparisons, but for the purpose of this report all cities are compared with a base city of New York, which has an index set at 100. The survey has been carried out for more than 30 years.

Methodology