Well this news blog is a bit late but always fascinating to look at what happened retrospectively. I thought this was entertaining. A lot of things going on in the first quarter. I split the blog in two pieces…

Here’s the Feng Shui financial forecast for 2018, the Year of the Dog

I thought this entertaining!!

Feb. 13, 2018, 9:57 PM

Wong Campion/Reuters

- The Chinese Year of Dog is a good time to be cautious when it comes to finances, according to this year’s CLSA Feng Shui Index.

- The guide, which farewells the Year of the Rooster, also includes top sector picks, property tips and zodiac predictions for health, wealth, love and careers in the Year of the Earth Dog.

- In terms of sectors, the index says to stick with pharma and consumer as the Earth Dog sees strong gains in wood-related industries overall.

- Telcos/internet, technology and utilities perform well but casinos and transport won’t get a leg up until October.

The Chinese Year of Dog is a good time to be cautious when it comes to finances, according to this year’s CLSA Feng Shui Index.

CLSA, a Hong Kong-based capital markets and investment group, has launched its 24th index, a tongue-in-cheek alternative look at what’s in store in the Chinese New Year.

The guide, which farewells the Year of the Rooster, also includes top sector picks, property tips and zodiac predictions for health, wealth, love and careers in the Year of the Earth Dog.

Feng Shui is a mystical system used in China seeking a balance between people and the elements of the world. Feng Shui masters are regularly consulted, sometimes at great expense, to make sure buildings about to be constructed are sited in harmony with its surroundings.

“The Dog represents duty and loyalty and is a sign of defence and protection,” says CLSA.

“It’s a good time to be level headed and to err on the side of caution. Entrepreneurs should stick with their most loyal clients, and investors are advised not to bite off more than they can chew.”

The path of the Hang Seng index as mapped by the Feng Shui experts:

CLSA Feng Shui Index 2018 CLSA

According to the index, there could be a stock market high ahead.

It says: “The Earth Dog jumps out of the kennel, tossing the Fire Rooster back to the barn and sending the Hang Seng index in Hong Kong skyward.

“After a great start, the hound takes a tumble in March which sees the Index head south.

“Through to summer the market chases its tail and drops, before the Dog and our favourite Earth Rooster, the HSI (Hang Seng index), extend a little more consideration towards each other and get back on track.”

In terms of sectors, the index says to stick with pharma and consumer as the Earth Dog sees strong gains in wood-related industries overall.

Telcos/internet, technology and utilities perform well but casinos and transport won’t get a leg up until October.

Investors who expect decent returns from banking and financials are definitely barking up the wrong tree this year,” says CLSA.

The Bitter Truth: Why Asia’s Tigers Suffer while the Nordics Thrive

Yulin Huang

Why you need to know

Justin Hugo looks at how statistics suggesting the Asian Tiger economies have caught up with their Scandinavian counterparts mask a more sobering wage-based reality.

Wage wars

The Asian Tigers and Japan have enjoyed a remarkable growth streak over the last half a decade that has put them firmly in the league of high-income countries – at least as measured by GDP per capita – a phenomenon bested by only some oil-rich Gulf states.

But in terms of the actual livelihoods of their citizens, have they caught up?

Nordic countries are upheld as the gold standard of what a model country should look like, often featuring in lists of the world’s best places to live with the happiest people in the world. How would the Asian Tigers – known on the contrary for their high stress levels and rates of suicide – compare with the Nordics, and with the Netherlands, which Taipei mayor Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) said is “an excellent model [… and] the best country for Taipei to learn from,” having realized that Taiwan’s thriving democracy discounts emulating the region’s leading economic light, Singapore.

“[Former] President Lee Teng-hui (李登輝) had led Taiwan along a “democratic path,” that meant [that Taiwan] could never be like Singapore,” Ko reportedly said. Taiwan and the Netherlands also have significant historical links dating back to when Taiwan was a Dutch colony (1624-1662), the Taipei mayor added.

But the growth spurt among the Asian Tigers did not happen all at once. Back in 1950, the real GDP per capita of Hong Kong, Japan and Singapore was already among the highest in Asia, at US$4,013, US$2,519 and US$2,439, respectively. Taiwan’s real GDP per capita was US$1,393 and South Korea’s US$1,122, according to data from the University of Groningen’s Maddison Project Database, which provides researchers with tools to compare economic performance between regions.

Source: University of Groningen

Meanwhile, the real GDP per capita of the Nordics and the Netherlands was twice at high, at between US$5,208 (Finland) and US$9,376 (Denmark) – they were already one of the richest countries in the world at that time.

SnSource: University of Groningen

Nearly 70 years later, in 2016, Norway’s real GDP per capita had grown to US$76,397 while Singapore’s had shot past the rest of the pack to US$67,180.

At the same time, Hong Kong’s real GDP per capita had grown to US$47,043, similar to the Netherlands’ US$49,254 and Denmark’s US$45,141, Taiwan’s had risen to US$42,304 which is comparable with Sweden’s US$44,371. Japan and South Korea real GDP per capita were roughly on par with Finland’s US$38,335.

Source: University of Groningen

One might assume that a similar level of national wealth might equate to citizens enjoying a similarly high standard of living, but this is where the GDP per capita statistics are misleading.

A more illuminating comparison involves looking at the minimum and median wages of each country.

Source (data from latest year): Norway: Norwegian Labour Inspection Authority, Denmark: 3F – Danmarks Stærkeste Fagforening, Sweden: Swedish Work Environment Authority, Finland: Service Union United PAM, Netherlands: Government of the Netherlands, Japan: Japan International Labour Foundation, South Korea: Pulsenews.co.kr (Maeil Business Newspaper’s English news site), Taiwan: Ministry of Labor Republic of China (Taiwan), Hong Kong: Labour Department The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, Singapore: Ministry of Manpower Singapore.

In the Nordics, there are no minimum wages – salaries are collectively bargained for by labor unions in different industrial sectors – which by the way, results in the highest wages in the world. According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), collective agreements cover about 90 percent of workers in Finland, 89 percent in Sweden, 84 percent in Denmark and 67 percent in Norway.

For the purposes of this comparison, we can use the wages of transport workers as the de facto minimum wages in the Nordics: Norwegians earn a monthly minimum of approximately 27,662.25 krone (US$3,517), the Swedes 25,088.00 krona (US$3,107) and the Finns €2,080 (US$2,542). For the Danes, workers in the industrial sector earn a minimum of 18,502.22 krone (US$3,039). In the Netherlands, where there is a nationally legislated minimum wage, it is €1,578.00 (US$1,929).

Turning to East Asia, Japan has the most respectable monthly minimum wage, at about 168,608 yen (US$1,524). South Korea’s historic minimum wage increase to 1,573,770 won (US$1,475) last year is also palatable.

So far, the minimum wages of these countries correspond roughly to their nominal GDP per capita, where the higher the nominal GDP per capita, the higher the minimum wage.

Source (data from latest year): Nominal GDP per Capita: The World Bank, Monthly Minimum Wage: Norway: Norwegian Labour Inspection Authority, Denmark: 3F – Danmarks Stærkeste Fagforening, Sweden: Swedish Work Environment Authority, Finland: Service Union United PAM, Netherlands: Government of the Netherlands, Japan: Japan International Labour Foundation, South Korea: Pulsenews.co.kr (Maeil Business Newspaper’s English news site), Taiwan: Ministry of Labor Republic of China (Taiwan), Hong Kong: Labour Department The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, Singapore: Ministry of Manpower Singapore.

Denmark, Sweden and Finland generally perform better by having minimum wages that are higher than the regression line, and the minimum wage increase that South Korea implemented last year elevated its position to a similarly lofty level.

Taiwan’s minimum wage of NT$22,008 (US$749) that took effect at the start of this year still leaves the country lagging below the regression line.

There are two other distinct outliers – Singapore and Hong Kong. Even though they have higher nominal GDP per capita than Taiwan, their minimum wage is set at a similarly depressed level – Singapore’s de facto monthly minimum wage is SG$1,100 (US$833) and Hong Kong’s is HK$6,724.74 (US$860).

In fact, Singapore does not have a minimum wage – basic minimum wages are set for the cleaning, landscape and security sectors but unlike the Nordics, the “minimum wages” set for these sectors are low – basic minimum wages for security officers are used for this comparison. According to Singapore’s Ministry of Manpower, these “minimum wages” are “developed by tripartite committees consisting of unions, employers and the government.”

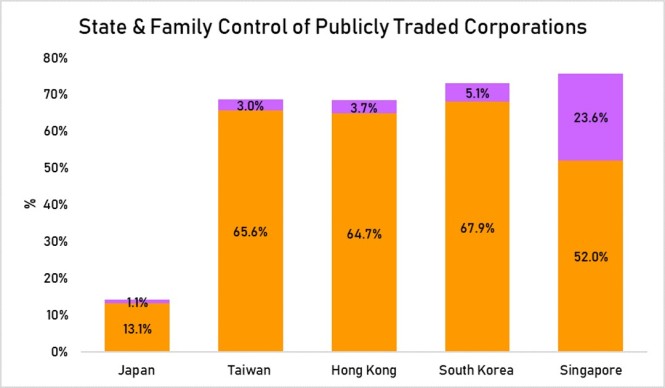

However, it should be noted that the government has its hands in the unions and businesses, which precipitates something more like a “one-partite” arrangement. The confederation of trade unions in the country – the National Trades Union Congress (NTUC) – is headed by a minister – Chan Chun Sing – who is widely tipped to be Singapore’s next prime minister. There is also high state control of publicly traded companies in Singapore – 23.6 percent as compared to only 1.1 percent, 3.0 percent, 3.7 percent and 5.1 percent in Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong and South Korea, respectively – though the figure for Taiwan is higher if you include companies indirectly controlled by state-owned shareholders.

Singapore’s nominal GDP per capita of US$52,963 is two times higher than Taiwan’s and puts it in between Denmark and Sweden. If Singapore were to adopt a similar minimum wage, it would be at least US$3,000 (SG$3,963) – or around US$2,300 (SG$3,039) if following the regression line above. Similarly, Hong Kong’s minimum wage should be closer to US$1,850 (HK$14,459) – on a par with the Netherlands, which has a similar level of nominal GDP per capita.

As such, low-income workers in Singapore and Hong Kong are being short-changed.

But the minimum wage does not give an overall perspective of the wage situation in these countries, so we also need to address median wages.

Source (data from latest year): Eurostat, Sweden: Statistics Sweden scb.se, Finland: Statistics Finland, Japan: (derived from Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Summary Report of Basic Survey on Wage Structure (Nationwide) 2012 and Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Year Book of Labour Statistics 2015, South Korea: The Hankyoreh, Taiwan: Focus Taiwan News Channel, Hong Kong: Census and Statistics Department The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, Singapore: Ministry of Manpower Singapore.

Norway has the highest monthly median wage (€4,562.37 / US$5,576) among the Nordics and the median wage in the Netherlands is €2,672 (US$3,226).

Japan has the highest median wage among the East Asian countries, of an estimated US$2,711, while Taiwan (NT$40,612 / US$1,382) has the lowest. South Korea’s (2,017,692.31 won / US$1,891) median wage is second-lowest.

As you can also see from the below, the higher the nominal GDP per capita, the higher the median wage as well.

Source (data from latest year): Nominal GDP per Capita: The World Bank, Monthly Median Wage: Eurostat, Sweden: Statistics Sweden scb.se, Finland: Statistics Finland, Japan: (derived from Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Summary Report of Basic Survey on Wage Structure (Nationwide) 2012 and Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Year Book of Labour Statistics 2015, South Korea: The Hankyoreh, Taiwan: Focus Taiwan News Channel, Hong Kong: Census and Statistics Department The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, Singapore: Ministry of Manpower Singapore.

Denmark (€ 3,828 / US$4,679) and Finland (€3,001 / US$3,668) have the second- and third- highest median wages in the Nordics and also sit above the regression line.

On the other hand, for Singapore and Hong Kong, median wages are considerably lower than trend. If median wages were to follow the regression line, Singapore’s should be closer to US$3,800 (S$5,020) and that of Hong Kong should be nearer to US$3,000 (HK$23,448), instead of the current S$3,500 (US$2,649) and HK$16,200 (US$2,073), respectively. In other words, the citizens of both cities should be earning a median wage of about US$1,000 more.

Whys and wages shares

What accounts for the discrepancy between wages and the GDP per capita in Singapore? If Singapore is considered one of the richest places in the world, why would its (de facto) minimum wages be among the lowest in high-income countries?

To see why, let’s look at the wage share of each country – or the share of GDP that goes to wages.

Source: OECD Statistics Working Papers, Taiwan: Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS), Executive Yuan, (R.O.C. Taiwan), Hong Kong: Hong Kong Economy The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, Singapore: Ministry of Trade and Industry Singapore.

We saw that Denmark, Sweden and Finland had de facto minimum wages that were higher than the regression line. One reason for this is their relatively higher wage shares – of 63.4 percent, 62.1 percent and 62.0 percent.

At the other end of the scale, Singapore’s wage share of only 42.5 percent explains why its de facto minimum wage is lower than the regression line.

Of note, too, is that Taiwan’s wage share is also low – at only 44 percent. As such, similar to Singaporeans, Taiwanese are not being compensated fairly for their labor, at least compared with high-income peers.

If the Taiwanese were paid a wage share of 50 percent – closer to the workers of South Korea (wage share of 51.8 percent) and Hong Kong (50 percent), then it follows by a back-of-an-envelope calculation that the minimum wage would also fall in line with theirs at about NT$25,000 (US$851). By the same logic, if wage share was elevated to the 60 percent level of Denmark, Sweden and Finland, then Taiwan’s minimum wage would amount to NT$30,000 (US$1,021)

Moreover, Chang Wen-po (張溫波), a former professor at National Taiwan University and retired department director at the Economic Development Council has shown in a Taipei Times article that when dividing Taiwan’s nominal GDP per capita last year by current wage share, the amount of NT$26,974 is actually lower than the NT$30,792 you would have obtained in the late 1980s and early 90s, when wage share was half of GDP. “[NT$30,792] would probably be acceptable for low-income earners [as a minimum wage],” he concluded.

Of course, a minimum wage of NT$30,000 (US$1,021) is “a dream” according to Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), who in a television interview recently declined to set out a timetable for when that dream might come true. Still, the fact that the figure is on the table is a step in the right direction.

Similarly, if Singapore’s wage share were to increase to 50-60 percent, minimum wages should correspondingly rise to between SG$1,230 (US$931) and SG$1,550 (US$1,173) – just a touch higher than in Taiwan under the same framework. But as explained previously, Singapore’s minimum wage should range between US$2,300 and US$3,000.

Inequality, poverty and corporate cultures

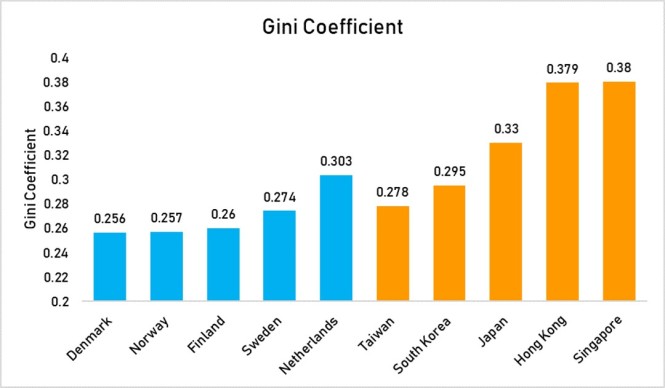

What is the cause of the large differentials in wage levels outlined in part 1? The reason lies in the Gini coefficient *. Singapore is the most unequal country among the developed nations – even when you include the United States and the United Kingdom.

Singapore also has the highest Gini coefficient, at 0.38 of the countries we are considering here. Hong Kong has the second-highest at 0.379 (derived from the Hong Kong’s Census and Statistics Department for comparison on OECD’s scale.)

By contrast, Denmark and Norway are the most equal countries in the world, with Gini coefficients of 0.256 and 0.257, respectively. (Note that the Gini coefficient figures account for taxes and transfers aimed at reducing the inequality – even so, Singapore and Hong Kong still present the largest income inequality.)

Source (data from latest year): OECD, Taiwan: Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS), Executive Yuan, (R.O.C. Taiwan), Hong Kong: Census and Statistics Department The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, Singapore: Department of Statistics Singapore

*The Gini coefficient; sometimes expressed as a Gini ratio (or a normalized Gini index) is a measure of statistical dispersion intended to represent the income or wealth distribution of a nation’s residents and is the most commonly used measurement of inequality.

You can see income inequality manifested in the gap between minimum and median wages. Because Singapore and Hong Kong have the highest Gini coefficient, they also have the highest wage gap – the median wage is 3.18 times higher than the de facto minimum wage in Singapore and 2.41 times higher in Hong Kong.

In Denmark and Norway, the median wage is 1.5 times higher – even so, de facto minimum wages in Norway, Denmark and Sweden are already higher than even median wages in the East Asian nations. Their workers already earn higher wages than half the population of the East Asian countries – because workers at the bottom in the Nordics start from a high wage base. South Korea’s wage difference is lower because of this year’s robust minimum wage increase. As a result, income inequality in South Korea could be even lower next year.

If Singapore’s inequality were reduced and the wage share returned to Singaporeans, you might see a wage distribution like that of Denmark and Sweden.

After all, Singapore has a nominal GDP per capita similar to both countries, and taking the median wage share of above 60 percent as a reasonable optimal level – and which Denmark and Sweden employ – and a Gini coefficient on par, then Singapore should have a similar wage distribution.

That would put the city state’s minimum wage at about US$3,000 (SG$3,963) or US$2,300 (SG$3,039) if it were to follow the regression line, instead of the SG$1,100 (US$830) we see now. The median wage would be around US$3,800 (SG$5,020), similar to Sweden, instead of the current SG$3,500 (US$2,635). Another way to look at it would be that if Singapore’s wage share were 60 percent instead of 42.5 percent, then Singapore’s median wage should correspond to US$3,720 (SG$4,914) – giving a similar result.

As for Taiwan, it has a comparable nominal GDP per capita to South Korea. By the same logic of adjusting wage share and Gini coefficient, this should give the country a similar minimum and median wage, putting the former twice as high as it is now, closer to US$1,500 (NT$44,078). The median wage would balloon to US$2,000 (NT$58,771) instead of the US$1,382 (NT$40,612) it is now.

Alternatively, if Taiwan’s wage share of 44 percent were increased to 60 percent, it would give the Taiwanese a median wage of NT$55,380 (US$1,884), achieving much the same result.

Is NT$40,000 as a minimum wage feasible? It is already being done on a localized level in Taiwan. A-Zen Bakery in Changhua County’s Lugang Township already gives its workers a minimum monthly salary of more than NT$40,000 a month. In fact, owner Cheng Yung-feng has increased his workers’ wages by 20 percent for the past two consecutive years, Taipei Times reported President Tsai as sharing. Because of that, the newest employees – who have two to three years of experience – have seen their salaries rise to more than NT$40,000 and are set to receive NT$48,000 this year. Workers who have been with the company for more than 20 years earn more than NT$100,000.

Now, A-Zen Bakery is an SME, yet it has the resources to give its workers significant wage increases and so far, it is still earning high profits, suggesting that Taiwan’s businesses do have a lot of leeway to increase the wages of Taiwan’s workers. In fact, in spite of the significant increase in wages, A-Zen Bakery continues to sell its buns at a low price of NT$20 and generates annual revenue of NT$50 million – resisting the temptation to raise prices along with wages. It is therefore not a question of how much the wages of Taiwan’s workers should increase, but how we can develop a roadmap to increase the wages of Taiwan’s workers to the ideal. As Tsai said, “Business owners should not think of raising wages as a burdensome increase to their overheads, but as a way for them to share their joy with colleagues who have worked hard to grow their businesses.”

According to Cheng, business owners and their employees are in the same boat. He believes that if everyone reaps the benefits together, employees would be more than willing to strive hard together with a company to help it succeed. His motto is, “The more we give, the more we get,” and as long as his company earns profits, he is happy to share them with his workers and increase their wages. Indeed, Cheng’s workers reveal that over the years, he has been giving the workers significant increases in salary, and because of that, not only has it done much to boost staff morale, they say that this has made them put in more effort to work harder for the company.

Salaries and poverty

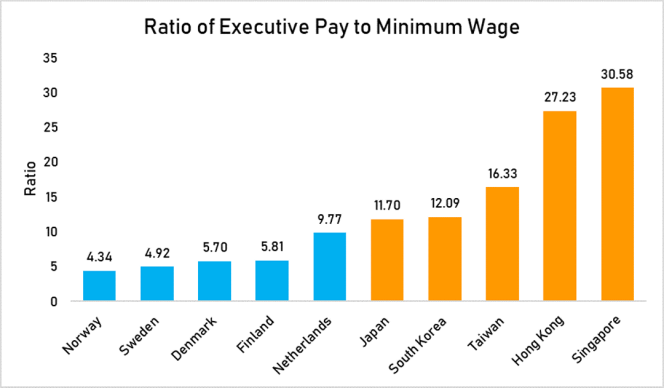

A comparison of salaries at the top makes the disparity even more glaring. Top executives in Singapore earn €250,000 / US$305,566 per annum (about €210,000 after taxes and social security – which is the second-highest net executive salary in the world). Those in Hong Kong earn about €230,000 (close to €200,000 after deductions, or the fourth highest).

In the Nordics, the Netherlands and Japan, executives earn about €150,000 to €185,000 per annum (or €115,000 to €125,000 after deductions in Japan and South Korea, respectively, and between €80,000 and €100,000 in the Nordic countries and the Netherlands).

Taiwan’s executives earn about €120,000 before taxes and social security but about the same as the Norwegians, Danes and Dutch after deductions – around €95,000.

Middle managers in Singapore and Hong Kong earn similarly higher salaries, both before and after taxes and social security, as the Nordic countries, the Netherlands and the other East Asian countries.

The fact that the Nordics have the highest “minimum wages” in the world but executive pay is relatively lower reflects how a fairer wage distribution helps reduce inequality.

Taiwan’s executives earn a similar net salary as their Norwegian and Danish counterparts but the minimum wage in Taiwan is only a fifth or a quarter of the de facto minimum wage in Norway and Denmark, which clearly shows the massive income gap in Taiwan vis-à-vis the Nordics. Taiwan’s low Gini coefficient therefore does not present a complete picture of Taiwan’s income distribution.

Singapore and Hong Kong also have one of the lowest minimum wages among the developed high-income countries – on par with Taiwan – but among the highest executive pay brackets in the world, helping explain the extremely high inequality that plagues the two cities.

This also explains the high level of poverty in both the cities.

Source (data from latest year): OECD, Taiwan: National Statistics, Republic of China (Taiwan), Hong Kong: The Government Information Centre The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, Singapore: Singapore Management University and Lien Centre for Social Innovation.

The Singapore government has refused to define a poverty line, claiming to fear an arbitrary “cliff effect”. However, a report by the Singapore Management University and Lien Centre for Social Innovation quoted Associate Professor Irene Ng from the National University of Singapore as estimating Singapore’s relative poverty rate to be about 20 percent, which would put the city as a leader in poverty among high-income countries.

This is perfectly plausible since Singapore has a de facto minimum wage that is even lower than Hong Kong’s and a cost of living ranked by The Economist as the highest in the world for the fourth year in a row in 2017 – Hong Kong’s poverty rate is 14.7 percent. Japan (16.1 percent) and South Korea (13.8 percent) have similar levels of poverty.

The Nordics and the Netherlands all have low levels of poverty, at between 6.3 percent (Finland) and 9 percent (Sweden).

Interestingly, Taiwan’s relative poverty rate is also low at 6.6 percent but this could be due to stagnant wages, which depress the median wage and therefore the relative poverty rate (which is defined by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) as half the median household income of the total population). On a similar note, Singapore’s depressed wages and the lower median wage could also result in a lower estimation of the poverty rate.

A better estimation of relative poverty would be to first define the optimal median income corresponding to the country’s GDP per capita, and calculating the poverty line from this optimal level – so, half of optimal median income. In Singapore, taking the optimal median wage as about US$3,800 (SG$5,020) would correspond with a poverty line at SG$2,500 (US$1,892). This puts more than 30 percent of the population in relative poverty. Professor Hui Weng Tat of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy estimated a relative poverty rate of around 35 percent based on a poverty line set at 60 percent of the national median equivalized income.

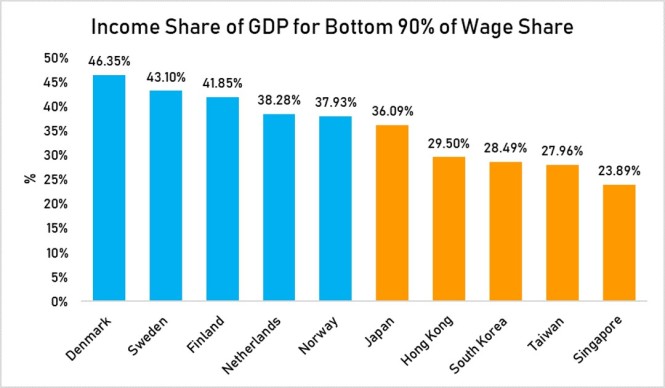

One other statistic gives us a broader perspective of the countries’ wage situation – the top 10 percent income shares.

Source (data from latest year): World Wealth & Income Database, South Korea: The Hankyoreh, Hong Kong: Education Bureau The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

Naturally, Singapore’s and Hong Kong’s high income inequality implies that the share of income that goes to the top 10 percent is one of the highest among the high-income countries – at 43.8 percent and 41 percent, respectively.

The top 10 percent income share in the Nordics and the Netherlands is lower, ranging from 26.9 percent in Denmark to 30.9 percent in the Netherlands.

Japan and South Korea’s top 10 percent income share is also high at 41.6 percent and 45 percent, respectively. However, they have relatively higher minimum wages, which should help close the wage gap, and the higher wage shares should enable a greater portion of the GDP allocated to wages to be available for fairer distribution, when compared with Singapore and Hong Kong. (Note that South Korea’s income share statistic comes from a separate source, and is used as an approximate.)

As a comparison, assuming the top 10 percent income share as a portion of the wage share, Chart 13 below shows the share of GDP that can be distributed to the remaining 90 percent of workers. For Singapore, this allows only 23.9 percent of the GDP to be distributed to the 90 percent of workers. In South Korea, it would be higher, at 28.5 percent, while Japan would register 36.1 percent. The shares are higher in the Nordics and the Netherlands. The share in Norway is slightly lower than the other Nordics because Norway starts off with a higher GDP per capita, and a higher income base.

In other words, because Singapore has a low wage share of 42.5 percent but 43.8 percent of the income goes to the top 10 percent, only 23.9 percent of the GDP would be available for the rest of the 90 percent as wages – based on our assumptions. In comparison, even though the top 10 percent income share in Japan is also high at 41.6 percent, but there is a high wage share of 61.8 percent, there is still 36.1 percent of the GDP that can be distributed to workers in terms of wages.

When we compare the difference between the annual executive pay and minimum wage, Singapore and Hong Kong again have the highest wage gap. Even though Taiwan’s wage disparity is not as wide, it still has the third highest gap ahead of Japan and South Korea.

Moreover, when comparing the pay gap between executives and middle managers (see chart below), the gap in Taiwan shows a similar disparity with Singapore and Hong Kong, suggesting that wages also fall off quickly from the top in Taiwan as well. Still, Taiwan’s income inequality is notably low as compared to the other East Asian countries, which could be due to the social welfare transfers that compensate for the wage gap, or the higher concentration of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) – we will look at these later.

Source: Approximate data of executive and middle manager pay from ECA International.

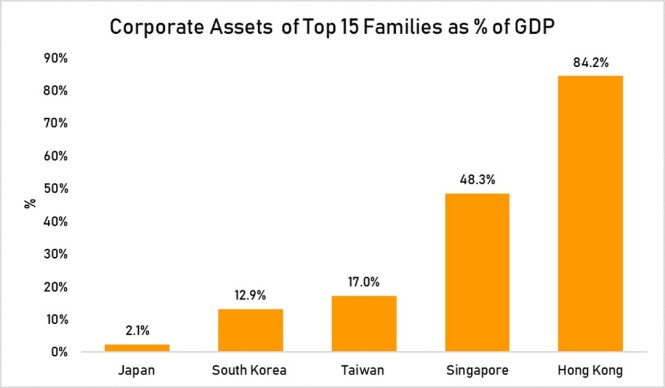

One possible reason why Taiwan’s executives and the rich pay themselves such high comparative salaries in relation to the minimum wage could be due to the control of top families in the largest firms. As can be seen in the chart below, two-thirds of the 20 largest firms in Taiwan were controlled by families (defined as having 10 percent control rights) in 1996. A similar pattern is also seen in Hong Kong and Singapore, with 70 percent and 45 percent, respectively – which helps further explain the high inequality in those cities. Taiwan’s Gini coefficient might therefore be relatively low due to the sharp drop-off in wages from the top which influences a more equitable wage distribution at the bottom. This idea led to a popular joke in Taiwan: “That wages are equal – because they are equally low.”

Taiwan’s low wages could therefore be attributed to the high family control which in spite of the country’s democracy has resulted in its economy functioning in a similarly familial fashion as Singapore and Hong Kong. But how does a politically-democratic and corporately-authoritarian country run? Could Taiwan’s relatively strong social welfare system but depressed wages and relatively poor labor standards in terms of rest days be a result of this odd combination?

Source (data from 1998 to 2000): Eklund, Johan E., and Sameeksha Desai. “Ownership and allocation of capital: Evidence from 44 countries.” Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics JITE 170.3 (2014): 427-452.

Among the Nordics, Sweden’s top families also have significant control in the top 20 largest firms – 55 percent – but the developed culture of collective bargaining for workers’ wages and a transparent democratic structure might serve to limit the families’ ability to expand their wealth at the expense of workers.

Fortunately, even as the top families in Taiwan have significant control in the largest firms, the corporate assets held by the top 15 families in Taiwan as a percentage of GDP is still not as high as Singapore and Hong Kong.

Source (data from 1996): Claessens, Stijn, Simeon Djankov, and Larry HP Lang. “The separation of ownership and control in East Asian corporations.” Journal of financial Economics 58.1 (2000): 81-112.

The concentration of control of the top 15 families comprised 17 percent of GDP in 1996, which is lower than in Hong Kong (84.2 percent) and Singapore (48.3 percent). However, it is still higher than Japan (2.1 percent) and South Korea (12.9 percent), which could explain the challenges faced by the Taiwanese in reforming their system for more equitable distribution, vis-à-vis Japan and South Korea.

Source (data from 1996): Claessens, Stijn, Simeon Djankov, and Larry HP Lang. “The separation of ownership and control in East Asian corporations.” Journal of financial Economics 58.1 (2000): 81-112.

However, as mentioned, Singapore stands out from other East Asian Tigers due to high state control – when looking at control of publicly traded companies in East Asia, 52 percent of companies are in family hands (with at least 10 percent of voting rights) while 23.6 percent is controlled by the state, effectively totaling 75.6 percent.

Source (data from 1996): Claessens, Stijn, Simeon Djankov, and Larry HP Lang. “The separation of ownership and control in East Asian corporations.” Journal of financial Economics 58.1 (2000): 81-112.

In South Korea, 67.9 percent of companies were controlled by families but only 5.1 percent were state-controlled. Similarly, in Hong Kong, it was 64.7 percent versus 3.7 percent and 65.6 percent versus 3.0 percent in Taiwan. In Japan, the control by both families (13.1 percent) and state (1.1 percent) is low.

But as Johan E. Eklund and Sameeksha Desai, authors of the study “Ownership and Allocation of Capital: Evidence from 44 Countries”, explain, “family control and ownership concentration negatively influence capital allocation. Economies with highly concentrated ownership structures display economic entrenchment and persistent misallocation of capital.”

There is evidence to support this. In “Performance for Pay? The Relation Between CEO Incentive Compensation and Future Stock Price Performance,” researchers found that “the longer CEOs were at the helm, the more pronounced was their firms’ poor performance.” Forbes reported the study’s authors as saying this is “because those CEOs are able to appoint more allies to their boards, and those board members are likely to go along with the bosses’ bad decisions.”

Among the Asian Tigers, the top firms are predominantly family-controlled (and state-controlled, in Singapore’s case), and the families’ (and state’s) voting rights of at least 10 percent effectively allow them to appoint their allies to company boards.

Michael Cooper of the University of Utah’s David Eccles School of Business, a co-author of the “Performance for Pay” study, added: “For high-pay CEOs, with high overconfidence and high tenure, the effects are just crazy” In fact, the returns on shareholder value of these companies over three years is 22 percent worse than their peers.

Indeed, long tenures are also a concern in Taiwan – a 104 Job Bank survey last year showed that 86.1 percent of Taiwanese companies polled do not have any succession plans while only 13.9 percent have thought of enacting one.

However, the problem also lies with how well executives pay themselves. Historian Nancy F. Koehn from the Harvard Business School suggests that in America, the salaries of board directors are usually decided by compensation committees, and since “Most board members of public companies are themselves well-paid executives … they have incentives to approve large pay packages for men (and the many fewer women) who are effectively their peers.”

Bloomberg writes up a very good summary of the thinking here.

In essence, the make-up of the companies in the Asian Tigers mean that they already function internally like compensation committees, and in conjunction with other families related to them, and via their intermarriages. Blogger Jess C. Scott has dug out and pieced together the relationships of the top families in Singapore from the corporate and political scene. Blogger Roy Ngerng had also drawn out several family tree maps of their relationships.

Koehn adds that these executives are “operating in a system that presumes the contribution of a good senior executive is very, very high.” But as we have seen from Cooper’s study, the evidence points to the contrary – “the more CEOs get paid, the worse their companies do over the next three years.”

In an analysis of American companies, former CEO Steven Clifford concludes that, “board directors and compensation committees have directly contributed to the rising salaries and bonuses of the country’s richest executives; [… but] each of those companies could have paid their CEOs 90 percent less and performed just as well.”

“From the outside, this may look a lot like cronyism or poor corporate governance, and no doubt both are at work,” says Koehn.

The Economist has calculated that Taiwan – and Singapore – has high levels of crony capitalism, at 3.2 percent and 10.7 percent of the GDP, respectively, when analyzing for billionaire wealth in the crony sector. In an earlier reiteration of the index, Hong Kong was also ranked as having the highest crony capitalism* level in the world, at 58 percent of the GDP. In comparison, Japan and South Korea have comparatively low levels of cronyism – at 0.6 percent and 0.5 percent, respectively. You can see a correlation between crony capitalism and the control of corporate assets within the top 15 families in the GDP.

Source: Corporate Assets of Top 15 Families: Claessens, Stijn, Simeon Djankov, and Larry HP Lang. “The separation of ownership and control in East Asian corporations.” Journal of financial Economics 58.1 (2000): 81-112., Crony Capitalism: The Economist, Crony Capitalism (Hong Kong): The Economist.

*Crony capitalism is a term describing an economy in which success in business depends on close relationships between business people and government officials. It may be exhibited by favoritism in the distribution of legal permits, government grants, special tax breaks, or other forms of state interventionism.

As The Economist explains, “Behind the crony index is the idea that some industries are prone to “rent seeking” […] when the owners of an input of production – land, labour, machines, capital – extract more profit than they would get in a competitive market.

“Rent-seeking can involve corruption, but very often it is legal,” it adds.

But Eklund and Desai offer this point of view: “We argue that it is not ownership concentration per se that creates inefficiencies in the allocation of capital but rather, key governing institutions. Therefore, strong private property and investor protection [will] reduce [the] equilibrium concentration ownership and improve [the] allocation of capital.”

In short, when wages are low and inequality is high, it is because of government inaction, and if wages are to be increased, then the government needs to act or citizens have to badger their government to do so, and hold politicians accountable for not acting on their promises to the citizens and workers, or for having too cosy relationships with big business.

The authors Stijn Claessens, Simeon Djankov and Larry H.P Lang, of the paper, “The separation of ownership and control in East Asian Corporations”, explain: “In most developing East Asian countries, wealth is very concentrated in the hands of few families. Wealth concentration might have negatively affected the evolution of the legal and other institutional frameworks for corporate governance and the manner in which economic activity is conducted.

“It could be a formidable barrier to future policy reform,” they conclude.

Singapore’s case therefore presents a danger to its citizens. Whereas in Norway the state also has a high control of publicly traded firms, there is transparency as to how these firms are managed and the Norwegian government is therefore accountable to its citizens and cannot withhold from them their rights and gains.

However, the Singapore government does not operate in a transparent manner. It was Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong who famously said: “I would not believe that transparency is everything” when discussing the government’s management of investment funds (which the country’s national pension funds are transferred into).

Social protections and saving graces

As touched on in part 3, Taiwan’s saving grace lies in its social welfare system.

Taiwan ranks eighth in a global list of unemployment benefit replacement rates*, which compare unemployment benefits received when not working to wages earned when last employed in a given year (in this case the year 2000). The list was compiled based on underlying data for this IMF working paper and does not take into account the eligibility of recipients for unemployment benefit, the duration they are able to receive it, or the conditions attached to its distribution.

Taiwan can be said to offer adequate protection, which at 60 percent of the previous salary is just below the Netherlands’ 70 percent, Sweden’s 68.5 percent and Norway’s 62.4 percent. In general, the Nordics and the Netherlands have high replacement rates, and they also start at a high wage base.

Singapore does not have any unemployment benefits – the government has refused to considerintroducing them on the basis that employers are mandated to pay laid off workers retrenchment benefits and Singapore has persistently low unemployment. Manpower Minister Lim Swee Say told Singapore’s parliament in 2016 that nine out of 10 retrenched workers receive such benefits.

Prime minister Lee Hsien Loong said at the May Day Rally in 2016: “Actually, we have something even better than unemployment insurance, because (for) unemployment insurance the worker has to pay out of his salary.” He added, “Ours is different. The scheme is not paid by the workers or the employers. It is paid by the government and the scheme is […] to help you get employed, get a job [and] upgrade yourself.” Lee was referring to the SkillsFuture scheme introduced in 2016 where Singaporeans aged 25 and above received SG$500 to attend training courses. However, this money is not given on an annual basis and Singaporeans only receive “periodic top-ups”. But early this month, it was revealedthat since its launch, only 285,000 working adult Singaporeans used SkillsFuture and in 2017, only about 160,000 Singaporeans, did so. The Online Citizen calculated that this would mean that only 11.4 percent of Singaporeans have used this money over the last two years – it would be lower when accounting for only 2017. It is not known if these figures account for the money which Singaporeans were scammed of – it was later found that SG$40 million worth of fraudulent claims to SkillsFuture were made by a criminal syndicate and 4,400 individuals submitted false claims of SG$2.2 million.

But academics, economists and opposition members have been calling for unemployment benefits. In the book, “Singapore Perspectives 2012: Singapore Inclusive : Bridging Divides”, published by the Institute of Policy Studies, the authors wrote that, “within policymaking circles, it is often argued that unemployment benefits create moral hazard, […] but even if our policymakers remain sceptical, […] how should our social security system help workers transit between sectors as the pace of restructuring intensifies?” At a budget forum organized by the Economic Society of Singapore in 2016, Assistant Professor Giovanni Ko at Nanyang Technological University also said, “You can’t just have a push towards automation without something to help catch these people who will probably lose their jobs,” and that, “there needs to be some kind of safety net”.

OCBC Bank’s head of treasury research and strategy Selena Ling echoed: “I think if you want people to take risks, you want people to give up their bread-and-butter kind of jobs to start up companies, try new things, see the world, fail nine times before they get one right … definitely you have to have some form of support infrastructure.”

Japan and South Korea’s unemployment benefits provide for only 28.9 percent and 25 percent of the previous salary, respectively, and in Hong Kong, it is only 41 percent.

It should be noted that in Japan, unemployment insurance is legislated at 50 percent to 80 percent of the previous salary but because there is a maximum daily limit of 7,830 yen (US$70.75) in unemployment benefits, the average gross replacement rate is therefore low in comparison with wages. Similarly, in South Korea, unemployment benefits cover 50 percent of the previous salary, and again because the maximum daily limit is only 40,000 won (US$37.48), the average gross replacement rate is low as well.

Source: European Welfare States blog (based on: IMF).

*Replacement Rates The replacement rate for given income levels measures the proportion of out-of-work benefits received when unemployed against take home pay if in work. While there is no pre-determined level of replacement rate which would influence every individual’s decision to work, clearly the higher the replacement rate, the lower the incentive to work. A replacement rate more than 70% is considered to be excessive.

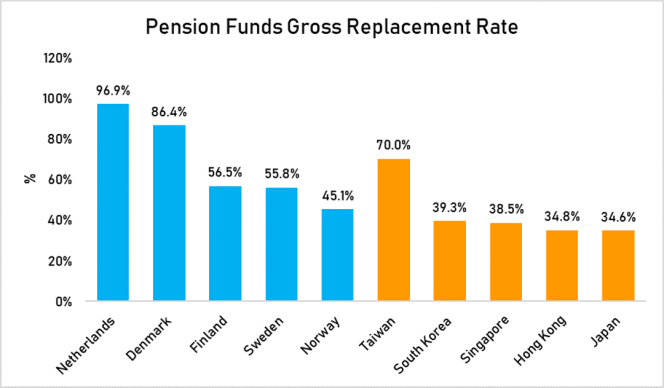

On pension adequacy, Taiwan also does well – the gross pension replacement rate stands at 70 percent, coming third after the Netherlands and Denmark, at 96.9 percent and 86.4 percent, respectively.

Source: OECD (2017 report), Taiwan; OECD (2009 report), Hong Kong and Singapore: OECD (2013 report).

However, there is a wide disparity in the pension payments received by Taiwanese workers. Before last year’s pension reform, the average monthly pension for public school teachers was NT$68,025 (US$2,315), NT$49,379 for military personnel and NT$56,383 for civil servants. However, for private sector employees, private school teachers only received NT$17,223 – just a quarter to a third of what their public sector counterparts received – while employees covered by labor insurance received only NT$16,179 and farmers received a paltry NT$7,256.

Moreover, 46 percent of retirees actually received an average pension of only NT$3,791 because they have not worked enough years to be eligible for pension payments. After the pension reform, the replacement rates for public teachers have decreased from 75 percent to 60 percent – still high – with a base pension payment amount of NT$32,160, which means that public school teachers will still receive at least twice as much as their private sector counterparts.

In addition, public sector workers already earn higher wages, a minimum of NT$29,345 as compared to NT$22,000 for private sector workers. Private sector workers in Taiwan are short-changed in terms of their wages and benefits.

The other East Asian countries fared poorly in their pension adequacy, with replacement rates at between 34.6 percent (Japan) and 39.3 percent (South Korea). Singapore’s and Hong Kong’s replacement rates were 38.5 percent and 34.8 percent, respectively. In addition to Hong Kong’s Mandatory Provident Fund (MPF) public pension scheme, the government also provides various social security schemes for the elderly based on their income level: 13 percent of the elderly received a monthly payment of HK$5,548 (US$710) in 2015, 37 percent received HK$2,390 and 19 percent received HK$1,235.

The amounts are actually low in comparison to the cost of living and do not do much to increase the replacement rates, but if you think these are low, look at what Singapore provides – only between SG$100 (US$76) and SG$250 a month, and it is only given to the bottom 20 percent of retirees, who have to meet stringent criteria. Retirees in Singapore are also not guaranteed a minimum pension amount or a minimum pension payment as a percentage of their previous wage as the other countries do. In 2014, the median pension payment from Singapore’s Central Provident Fund (CPF) was only SG$394, as compared to the median wage of SG$3,276 in that year, making up only 12 percent of the median wage.

The Singapore government transfers Singaporeans’ CPF pension funds into the government investment firm GIC Private Limited. The fund claims on its website that it “receives funds from the government […] without regard to the sources” while the Singapore government claims that the funds from the CPF are “comingled” with other funds such as government surpluses and land sales, and ultimately transferred to GIC for management.

The other government investment firm, Temasek Holdings, clearly states that “Temasek does not manage CPF savings.” There is little transparency in how the GIC and Temasek are being managed, and the size of the funds managed by the GIC are not even published. In 2015, Nominated Member of Parliament Chia Yong Yong said that she was “not entirely sure” if Singaporeans “have the right to spend [their CPF monies]” because “at the end of the day […] I am not the only person contributing to that fund, I cannot be the only person to call the shots as to how I’m going to spend it.”

Prime Minister Lee later said that Chia “made an excellent speech about the CPF” about the “broader perspective: whether it is right to think of the CPF as “our money”, to be spent solely as we choose.”

“I am glad that she did, and to such good effect,” Lee added.

Singaporeans have often complained that their CPF monies are trapped inside the government’s coffers and it has become commonplace to hear Singaporeans lament that the “CPF is not my money.”

Healthcare

On health expenditure, the Taiwanese government’s contribution of 60 percent of total health expenditure again puts Taiwan ahead of Singapore and Hong Kong, where the governments only spend 52 percent and 49 percent, respectively. However, Taiwan is still some way off from the governments of the Nordics, the Netherlands and Japan, which spend between 77 percent and 85 percent on healthcare.

Source (data from latest year): World Health Organisation, Taiwan: Ministry of Health and Welfare Taiwan, Hong Kong: Food and Health Bureau The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

Also in the Nordics, the Netherlands and Japan, there is an annual maximum payment limit that citizens need to pay when they seek healthcare, or a limit to the co-payment. Citizens in these countries only need to pay a maximum of between US$409 (Sweden: 3,300 krona) and US$845 (Finland: €691) in a year. It is higher in South Korea, where the limit is set at 2 million won (US$1,874) for the bottom 50 percent, 3 million won for the middle 30 percent, and 4 million won for upper 20 percent.

There is also an annual limit in Taiwan, but the cap of NT$59,000 (US$2,008) pertains to each condition, though it is understood that patients seldom have to pay this maximum amount. Patients pay as low as NT$50 (US$1.70) to see a general practitioner (GP) or NT$150 (US$5.10) for emergency care at a district hospital.

Source (data from latest year): Norway: The Local Norway, Denmark: Danish Medicines Agency, Sweden: The Newbie Guide to Sweden, Finland: City of Helsinki, The Netherlands: Zilveren Kruis, Japan: Tokyo Securities Industry Health Insurance Society, South Korea: National Health Insurance Service South Korea, Taiwan: National Health Insurance Administration, ROC, Hong Kong: Hospital Authority.

In Hong Kong, there is no annual limit set, but the government mandates specific charges that patients only need to pay when they seek healthcare at public hospitals. These charges are relatively low, ranging from HK$50 (US$6.40) for general outpatient services to HK$180 (US$23) per attendance to the Accident and Emergency.

Again, Singapore stands out for not having such protections – there is no annual payment limit. In the GP Fee Survey in 2013 published last year by the Singapore Family Physician journal, it was found that the median consultation fee was SG$35 (average of SG$40) with fees going up to as high as SG$100 (US$75.70).

Citizens have been known to pay astronomical amounts for healthcare – in fact, in 2012, it was foundthat 2,400 Singaporeans had to pay more than SG$10,000 (US$7,570) for their hospital bills. A studyby Associate Professor Tilak Abeysinghe and then-PhD student Himani Aggarwal in 2014 also showed that as early as 2007, of 30,192 cases of elderly patients hospitalized at a public hospital, there were seven cases where the net hospital bill after government subsidies exceeded SG$100,000 (US$75,670), where the highest was SG$207,741 (US$157,259). In fact, Singaporeans have been known to “choose death over dialysis when their kidneys fail,” one reason being that dialysis is too expensive. It is preposterous that whereas other countries set a limit as to how much citizens have to pay for healthcare, the Singapore government instead sets a limit as to how much citizens’ can claim for healthcare.

In contrast, it is free for citizens to see a GP in Finland, Denmark and the Netherlands. In Sweden, it is between 100 krona (US$12.39) and 300 krona (US$37.16), and between 152 krone (US$19.32) and 257 krone (US$32.67) in Norway. In Taiwan, it is only NTS$50 (US$1.70). In Singapore, median and average consultation fees in 2013 were SG$35 (US$26.49) and SG$40 (US$30.27), respectively, but can go as high as SG$100 (US$76).

In Japan, people who go to the GP only need to pay 20 to 30 percent of the costs, while in South Korea, it is 30 percent. In Singapore, the average citizen stumps up the full cost.

In almost all these countries, there is a maximum limit for how much citizens need to pay for patient fees in a year, but again, there is no such ceiling in Singapore.

A Lancet study has shown that high co-payments and hospital bills increase “potentially avoidable hospital admissions due to worsening of the condition, or emergency visits to obtain medication in acute episodes in patients with chronic diseases. Co-payments reduce demand for preventive services, because people tend to overestimate present costs and underestimate future health benefits.” This results in patients still having to go to hospital and pay even more than they would initially.

Unless they choose to die – which some Singaporeans have opted to do.

This could be why Singaporeans have developed a “kiasu” and “kiasee,” or fight or die, attitude. But this has created a self-centered culture – studies have shown that given Singapore is the most unequal country among the developed nations, Singaporeans are also less trusting towards one another and the level of self-enhancement – where people believe that they are better than someone else – is also the highest among developed nations. Social mobility in Singapore is impeded because of the city state’s unequal social and economic structure.

On the other hand, even though wages in Taiwan are the lowest in this comparison, the country in fact offers a solid social safety net – even though it might not seem so to some Taiwanese. By most metrics, Taiwan’s social welfare system can be considered a strong one – it just does not feel like it because low wages make the benefits look insufficient.

It should also be noted, however, that Taiwan’s government pays for only 60 percent of health expenditure, which compared to other developed countries, is relatively low. As such, there is room for the government to increase spending to between 70 and 85 percent, so that the quality of Taiwan’s healthcare system can be maintained, and is not compromised by unnecessary cost-cutting measures. As such, instead of reducing the top rates of income tax, the Taiwan government would do better to redistribute the budget to improving healthcare standards. This could begin with improving the quality of life of healthcare workers by hiring more of them – Taiwan already has the lowest physician densityamong the high-income countries – tied with Singapore and Hong Kong. Their governments spend the lowest among the developed countries on healthcare.

Source (data from latest year): World Economic Forum, Hong Kong: Department of Health The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

On paper, Taiwan stands out as a place that protects its poor and sick. That’s a saving grace, at least.

Equality and the future

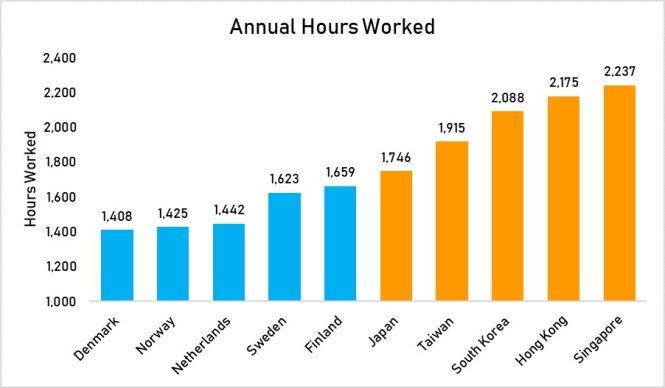

There is an important area in which East Asian countries still have not caught up and perform poorly as a whole – work hours and off days.

Source (data from latest year): The Conference Board.

In terms of work hours, Singaporeans work the longest among the developed countries – 2,237 hours annually. People in Hong Kong work the second-longest, at 2,175 hours, while South Korea comes in third at 2,088 hours. Taiwanese endure long hours as well, but not to the same extent as their counterparts in the other Asian Tigers do, clocking in 1,915 hours per year.

Japan fares a bit better, but it is the Nordics that shine – after the Germans, the Danes, Norwegians and Dutch work the shortest hours in the world.

Source (data from latest year): Central Intelligence Agency

It would also be reasonable to conclude that the situation for low-income workers in Singapore is completely out of whack – they earn comparatively low wages, work long hours and can only take short breaks, but suffer from scant social protection. Workers have limited protection from unemployment.

Singapore’s harsh inequality therefore also results in the country having one of the lowest purchasing powers (as measured by purchasing power parity*) when compared with the high-income countries. Even though Singapore has one of the highest GDPs per capita in the world, because the wage share is low and inequality is high, wages are therefore relatively low. This, coupled with being the most expensive place to live in the world, equates to low purchasing power. If it is of any consolation to Singaporeans, Taiwan has a lower purchasing power, though Taiwan’s redeeming feature is that it has a stronger social welfare system. On the other hand, precisely because the Nordics have one of the highest GDPs per capita in the world, and these countries have a high wage share and the lowest income inequality in the world, they therefore also have the highest purchasing power in the world after Switzerland and Australia and enjoy a high standard of living that is only available to the rich in Singapore and Hong Kong.

Source (data from latest year): World Economic Forum

Purchasing power parity (PPP) is an economic theory that compares different countries’ currencies through a “basket of goods” approach. According to this concept, two currencies are in equilibrium or at par when a basket of goods (considering the exchange rate) is priced the same in both countries.

Singapore’s socio-economic structure embodies many of the fundamentalist views on eugenics expressed by Singapore’s first prime minister Lee Kuan Yew. In 1969, the late Lee said in parliament: “free education and subsidized housing lead to a situation where less economically productive people in the community are reproducing themselves at rates higher than the rest.”

In 1980, as the birthrate among women who were more educated fell faster than that of those who were less educated, Lee then said: “If we continue to reproduce ourselves in this lop-sided way, we will be unable to maintain our present standards. Levels of competence will decline. Our economy will falter; and administration will suffer; and society will decline.”

The irony is that it is these very beliefs that have resulted in Singapore developing along such unequal lines. Singapore’s government has implemented these ideas to their full extent, treating the poor with contemptible disdain. If “society will decline” – as Lee put it – then it is because of his own ideals. By marginalizing the poor and denying them opportunities to move up the social ladder – Singapore’s social mobility is low because of its inequality – the Singapore government reinforces structural poverty. The poor cannot move up not because they do not want to, but because they are not allowed to. The examples of the Nordics show that that where resources are distributed equally, and everyone is uplifted, society progresses together. Whether or not the current leaders in Singapore subscribe to the late Lee’s views, they have continued to indulge them.

In truth, it is not because people are “less educated” that makes them poor, it is their poverty that makes them “less educated.” A study in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine found that people who are consistently exposed to having low incomes for two decades showed worse cognitive function and intelligence levels, and that living in poverty and hardship also meant a higher possibility of premature aging.

Research from Princeton University suggests that people who are poor are not less capable because of any inherent traits but because poverty impedes their cognitive capacity. The researchers explain: “Poverty and all its related concerns require so much mental energy that the poor have less remaining brainpower to devote to other areas of life.”

The researchers go on: “Thusly, a person is left with fewer mental resources to focus on complicated, indirectly related matters such as education, job training and even managing their time.” As a result, the poor “make mistakes and bad decisions” because they are poor – and must spend too much time thinking about how to make ends meet. It might take having to fall into poverty for people to really appreciate what this means.

But the study also shows that when people are lifted out of poverty, “low-income individuals performed competently, at a similar level to people who were well off,” then doctoral student and co-author Jiaying Zhao explains. As such, people who are considered intelligent now but who are made to live in poverty can also become less intelligent, when their resources are constrained. It is not a zero-sum game and definitely does not conform to the eugenics ideology expounded by the late prime minister.In sum, our society can be smarter as a whole when people are paid higher wages, and when resources are more equitably distributed to let everyone have the same chance. Unfortunately, the ruling People’s Action Party appears too deeply embroiled in the situation to pull itself out and Singaporeans are too fearful – or complacent – to do anything about it.

Taiwan’s future

Taiwan, on the other hand, by its metrics, has a relatively strong social welfare system, with high adequacy in unemployment benefits and gross pension replacement rates, as well as healthcare that is generally cheap.

However, the key issue with Taiwan is low wages, which drag down Taiwan’s otherwise strong social welfare system. It has thus become commonplace to read reports or hear government officials talk about how the national health insurance or pension system might go bankrupt, but this neglects the wage issue, which results in lower contributions to Taiwan’s social welfare system.

But Taiwan is on the crux of change. Should the country continue down the misguided path of neoliberalism and inequality, which even the IMF is now cautioning against, or focus on pursuing progressive ideals as part of its democratic evolution?

When Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) was elected, she promised to increase workers’ wages.

“Our young people still suffer from low wages. Their lives are stuck, and they feel helpless and confused about the future,” she said.

Indeed, Commonwealth Magazine wrote about the 30-somethings in Taiwan who grew up during as wages became depressed, and because of that, Lin Thung-hong, an associate research fellow in Academia Sinica’s Institute of Sociology, explains, “(Living in the moment) is rational behavior when wages are low because saving doesn’t have any benefits.”

Therefore, when Hsu Chung-jen (徐重仁), president of PX Mart, one of Taiwan’s largest supermarket chains, complained that Taiwan’s youths were “spending too much money” and that they should “tolerate rather than complain about low pay,” he could not be more out of touch.

“Nowadays, young people are really spendthrift,” Hsu said, “Young people should not fuss over having lower salaries than other people. Withstand rather than complain; work diligently and your boss will see you one day.” But have the bosses of Taiwan met his expectations?

Hsu later apologized, saying “the incident led him to reflect whether he — and those of his generation — tend to pass judgement too quickly on the younger generation,” Taipei Timesreported him as saying.

Perhaps Hsu might not be completely to blame for his lack of understanding. As in Singapore, the rich-poor gap in Taiwan has also resulted in a separation of experience and understanding, where “the Elites – due to their wealth – do not suffer the detrimental effects” of inequality and “appear to be oblivious” to the plight of those at the bottom, as a study on collapsed societiesexplains.

Taiwan and Singapore are of course different – Taiwan is a democracy where its citizens have the right and ability to push for change. In Singapore, activists have been intimidated,interrogated, sued, charged and jailed, while some have lost their jobs simply for speaking up – just like in China.

Taiwan president Tsai also said at her inauguration: “Young people’s future is the government’s responsibility. If unfriendly structures persist, the situation for young people will never improve, no matter how many elite talents we have. My expectation is that, within my term as president, I will tackle this country’s problems step by step, starting with the basic structure.”

Compare this with Singapore’s Prime Minister Lee who mocked income inequality as a “fashionable thing to talk about.”

He also said: “If I can get another 10 billionaires to move to Singapore and set up their base here, my Gini coefficient will get worse but I think Singaporeans will be better off, because they will bring in business, bring in opportunities, open new doors and create new jobs, and I think that is the attitude with which we must approach this problem.”

Well, statistics suggest otherwise.

President Tsai also campaigned on a platform of marriage equality in the last general election, yet her administration has dragged its heels on following through. Premier William Lai (賴清德)said in October last year that the Legislative Yuan was still working on submitting a proposal on marriage equality for discussion before the end of 2017 but we are now into the new year, and not a sound has been heard. Nonetheless, Taiwan remains the only Asian country which has a road map towards marriage equality by the middle of 2019 – putting it in the same league as the Nordics and the Netherlands, even as its East Asian counterparts remain nonplussed by the issue.

| Same-sex marriage recognition (year of legalization) | No same-sex marriage recognition | Criminalization of male same-sex sexual relationships |

| Netherlands (2001) Norway and Sweden (2009) Denmark (2012)Finland (2017) | Japan (partnership certificates issued in six local governments)

Hong Kong and South Korea-none |

Singapore |

In Singapore, after a record number of international corporate sponsors joined in the eighth run of the annual PinkDot SG event in 2016, held in support of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) community, the government announced that foreign entities would not be allowed to sponsor the event unless they apply for permission. Even then, Google, Apple, Facebook, Salesforce, Airbnb, Uber, Microsoft, NBC Universal and Goldman Sachs did just that,but had their applications rejected. The government also introduced new rules to prohibit foreigners from participating or to sponsor the event. Those deemed to be illegally participating can be fined while organizers are threatened with fines and jail time if they flout the rules.

However, the ban has had the opposite effect – more than 100 local companies then stepped up to provide sponsorship for the event. Still, male same-sex sexual relationships are still illegal even though the ILGA-RIWI Global Attitudes Survey on Sexual, Gender and Sex Minorities released last year showed that 61 percent of Singaporean participants believe that equal rights and protections should be applied to people who are romantically or sexually attracted to people of the same sex – which was the second-highest acceptance level in Asia.

In Hong Kong, the High Court said in a landmark ruling last year that the government should provide the same benefits that it provides to heterosexual couples, to same-sex couples. Justice Anderson Chow Ka-ming (周家明) called the Civil Service Bureau’s policy “indirect discrimination” – the bureau had denied benefits to senior immigration officer Leung Chun-kwong and his partner, Scott Adams from New Zealand, whom he married in 2014, claiming the need to protect “the integrity of the institution of marriage”, leading Leung to challenge the bureau in court. However, the government has decided to appeal the ruling.

In South Korea, homosexual activity is banned in the military and after a video showing two male soldiers having sex was uploaded onto social media, human rights group reported a witch hunt against gay soldiers which even used dating apps to entrap them, leading to 32 soldiers being charged. The Associated Press also reported the South Korean President Moon Jae-in as opposing homosexuality.

On the other hand, in Japan, partnership certificates can be issued to same-sex couples in six local governments and the city of Sapporo, even though they are not legally recognized as marriage certificates. Attitudes towards homosexuality are said to be conservative, though the ILGA-RIWI survey also showed that 55 percent of participants believe that same-sex couples should be treated with equal rights and protections.

Overall, among the Asian Tigers, Taiwan is a mixed bag. On the one hand, wages are low but on the other, Taiwan has a good social welfare structural system and same-sex marriage will soon be legal in the next one and a half years at most. It seems almost as if the Taiwanese government is pushing all the right buttons except the most important one – wages (and related to it, rest days).

Vice Premier Shih Jun-ji did discuss the possibility of increasing wages by 6 percent every year to achieve a minimum wage of NT$30,000 (US$1,021) by 2024, or by 8 percent to achieve it by 2022. However, Shih’s calculations do not consider the inflation rate, which in 4 years time might mean minimum wage should have gone up to NT$32,000 (US$1,089), which would mean that wages should be increasing by 9 to 10 percent every year – noting the study mentioned earlier which showed that a 10 percent increase would only lead to a 0.4 percent increase in overall prices and 4 percent in food prices.

Taiwan’s government should come out with a projection as to the different scenarios that wages can be increased by, and how these would affect prices and employment, so as to come out with a practical solution.

Even so, Premier William Lai had side-stepped the topic of implementing a minimum wage of NT$30,000 even as he suggested that listed companies and multinational corporations should pay graduates a starting wage of NT$30,000. But a minimum wage policy is important as can be seen in the announcement of the Workforce Development Agency (WDA) annual career fair. At its upcoming fair, of the 3,500 jobs available, only half will have a starting salary of NT$30,000 per month. In spite of Lai’s calling on businesses to increase starting salaries to NT$30,000, this call has not been heeded – which is why increasing minimum wage as a policy is necessary.

While NT$30,000 is not only the “ideal” minimum wage, it is also necessary to bring Taiwan’s wages to parity. Taiwan’s current minimum wage is only NT$22,000, but public-sector workers already earn a minimum of NT$29,345 and with the pension reform last year public sector pensioners are also guaranteed a minimum pension payment of NT$32,160.

Clearly, the government acknowledges that NT$30,000 to NT$32,000 is the minimum necessary for basic living for the Taiwanese. Leaving private-sector workers in the lurch to earn only NT$22,000 and leaving it to the private sector to increase wages without legislating minimum wages to the ideal would be irresponsible.

In fact, when you take the example of Denmark and Sweden, public and private-sector workers earn about the same wages, and skilled private-sector workers actually earn higher wages than public-sector workers, so it begs the question why public sector workers in Taiwan are earning such significantly higher wages than private-sector workers. Shouldn’t they be earning similar – and higher – wages if the Taiwanese are to be uplifted together? Which is why the continuous push by retired public servants to fight to keep their high pension payments – which already would put them in the top 10 percent income earners – is incredulous.

What kind of example are the public school teachers setting for their students when they would fight for their own pension and not for the general public, when the very people they teach would go out into the workforce to earn significantly lower pay than them? Already, public school teachers already received an average pension of NT$68,025 last year, or 18 times higher than the average pension of only NT$3,791 that 46 percent of Taiwanese retirees were able to receive. Shame is perhaps not the right word, but where we should work for the benefit of all of Taiwan, where is the self-respect of the public school teachers when their role should be to educate the public of their responsibility to society?

Shih also said that the government would adopt a targeted approach to increase minimum wages in industry sectors where wages are low such as in the retail and food industries, and where unemployment is high such as among young workers and first-time job seekers, instead of a “broad approach aimed at improving the entire economy.”

But labor unions should take note – the Nordic example where collective bargaining is done for each sector actually helped to increase wages to the highest in the world, but that is because they are democracies. Taiwan may be a democracy, but it has not attained the level of transparency that the Nordics have and because the top families’ control of businesses in Taiwan is similar to Singapore’s top families’ (and state’s) control – and where crony capitalism is high. Taiwan might fall into a similar situation where wages would remain low as in Singapore’s case, even if there were any increase. Where Taiwan will go depends on the integrity of Taiwan’s politicians and their commitment to democracy, and the strength of the labor unions and the Taiwanese to hold the government accountable.

The World Economic Forum highlighted this: “Recent empirical research indicates that the most important explanation for the falling wage share is workers’ weaker bargaining position.”

It added that, “The conclusion is that it is absolutely possible to restore the wage share through the right policies, [… by] strengthening the welfare state, supporting trade unions and providing workers with […] a social safety net,” among other things.

Additionally, the Nordic model has shown how high wages and a strong social welfare system can help design an ecosystem which has led the Nordic countries to be one of the most innovative in the world, and which has moved the Nordic countries into high-skilled and high-value industries.

At the very least, at her year-end conference, President Tsai did talk up her promise of setting a minimum wage act.

Tsai also said: “The government will provide support to companies willing to give bigger pay raises. When companies share more of their profits with employees, this increases employees’ buying power, creating a positive cycle that benefits both enterprise and labor.”

Tsai’s point is backed up by evidence which showed that “the marginal propensity to consume of high-income earners is substantially less than for low-income earners,” as reported by The Guardian of the study by Brookings Institution and the Reserve Bank of Australia.

GoBankingRates.com also showed that the richest 10 percent in America actually spends about the same on basic necessities as the rest of the 90 percent – US$1,601 vs US$1,455, respectively, but with the top 10 percent spending only 10 percent of their income. As such, Michael Linden of the Center for American Progress’ managing director for economic policy told HuffPost: “It’s a real problem to the extent that more and more income is going to people at the top and more of that income is not going to places that are productive.”

Sam Pizzigati, an associate fellow at America’s Institute for Policy Studies added that, “This whole hoarding episode [among the rich] just tells us once again that any society that lets wealth concentrate at the top is making a very foolish move economically.”

“There’s a bit of a vicious cycle,” Linden said. And this is where Taiwan is today.

For too long, Taiwan’s government has pandered far too much to the big businesses. This has resulted in a vicious cycle, as Tsai’s proposal hopes to undo, or at least we hope it will. But this also requires the cooperation of the top families in Taiwan and the bosses of SMEs to understand the role they play not only as business leaders but as the citizens of Taiwan. If Taiwan is to become relevant on the international stage again, the Taiwanese have to first take themselves seriously and to uplift the livelihoods of one another, so that the Taiwanese will gain a new confidence and foothold and be able to take Taiwan forward together as a nation.

On many indicators, Taiwan already performs admirably – in terms of social welfare and human rights. But if Taiwan were to truly become one of the developed and democratic countries in the world, it has to start with wages – by increasing them.

The World Economic Forum explained: “Strong unions, collective wage bargaining and high minimum wages can offset the negative impact of other factors, as the Nordic countries have proved,” which together can help design an ecosystem which has led the Nordic countries to be one of the most innovative in the world, and which has moved the Nordic countries into a high-skilled and high-value industry.

The solution therefore, is doable. Writing before the recently-concluded World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2018, Executive Director of Oxfam International Winnie Byanyima said: “I will be urging political leaders [at the meeting] to limit rewards to shareholders and senior executives, introduce a statutory living wage, build fairer tax systems, invest in healthcare and education, and shepherd in a technological revolution that works for all. I will be calling on business leaders to stop paying huge share dividends and awarding bumper pay packages to top executives until they can guarantee that all of their workers are getting a living wage and that their suppliers in their supply chains are being paid fair prices.”

The same needs to be done in Taiwan.