South-East Asian integration

More hat than cattle

A seamless regional economic bloc is just around the corner—as always

Jan 2nd 2016 | SINGAPORE | From the print edition

Opening up, ASEAN-style

GRANDIOSE statements from the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) are the region’s Christmas crackers: they appear at regular intervals, create a commotion but contain little of substance. In November the leaders of the club’s ten members declared that the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC)—a single market around which goods, services, capital and “skilled labor” are supposed to flow freely—would come into being on December 31st.

So will South-East Asia’s 622m people wake up in a new world in 2016, or will the AEC prove another paper crown?

The answer probably lies somewhere in the middle. For one thing, much of the work towards economic integration has been done: by ASEAN’s reckoning, 79.5% of the measures the AEC involves have already been implemented. ASEAN already attracts large amounts of foreign investment, and its leaders have been talking up integration and regionalism since the organization was founded in 1967. So the AEC represents less a radical change than an attempt to accelerate existing trend

But anyone hoping that ASEAN is about to turn into an Asian version of the European Union will be disappointed. European integration is fundamentally a political project with an inward focus, argues Jayant Menon of the Asian Development Bank, which has led to a mushrooming of institutions. The AEC, in contrast, is an economic project, with almost no institutional heft—just a small secretariat—devoted to “outward-oriented regionalism”. It is designed to make the region an easier and more attractive place for foreign companies to do business and thus to boost trade and investment.

Those missions are helped by ASEAN’s economic dynamism. Between 2007 and 2014 regional GDP doubled, from $1.3 trillion to $2.6 trillion, and GDP per person grew from $2,343 to $4,135. Total internal and external trade grew from $1.6 trillion to $2.5 trillion, and foreign direct investment rose from $85 billion to $136 billion. Viewed as a single economy, ASEAN is the world’s seventh-largest and Asia’s third-largest, behind China and Japan. And while China and Japan are ageing rapidly, ASEAN remains young, with more than half its population under 30. China’s slowdown has taken its toll on the region—particularly on commodity exporters such as Malaysia and Indonesia—but its young workforce, improving infrastructure and rising incomes leave it poised for strong future growth.

Behind those aggregate figures, though, lie vast differences, not all of which are conducive to economic integration. Vietnam and Laos are communist dictatorships; Brunei an absolute monarchy; the Philippines and Indonesia rowdy democracies. Singapore was founded as a trading entrepot (or trans-shipment port) in 1819; Indonesia has a history of protectionism. Perhaps inevitably, the commitment of such a diverse bunch to regional integration, and the pooling of sovereignty it implies, is not as strong as ASEAN’s triumphant statements suggest.

There is no mechanism to enforce the group’s many agreements and treaties. Regional banking systems and capital markets remain unintegrated. Tariffs may vanish, but non-tariff barriers pop up in their place. Members continue to set their own intellectual-property, land-use and immigration policies.

The rules regarding the free movement of “skilled labor” provide a good illustration of the AEC’s limitations. Under its mutual-recognition arrangements (MRAs), certain professional qualifications from any member are deemed valid in all the others, allowing holders of them to work throughout the region. But the AEC’s MRAs cover only eight professions, accounting for just 1.5% of ASEAN’s total workforce. Moreover, even in these fields, other domestic regulations inhibit foreign workers. Nursing, for instance, is among the eight professions subject to an MRA, but to work in Thailand nurses still must pass a qualifying exam in Thai. As Mr. Menon points out, this is short-sighted: English-speaking Filipino nurses would be a boon to Thailand’s burgeoning medical-tourism sector.

Knitting South-East Asia together economically sounds appealing, but the political will to make it happen is hard to find. For the moment, ASEAN seems more focused on the letter than the spirit of regional integration.

Global inflation

Low for longer

Inklings of inflation in the rich world are outweighed by downward pressure on prices elsewhere

Jan 2nd 2016 | From the print edition

EVER since the financial crisis of 2008, forecasters have scanned the horizon for the next big disruption. There are plenty of candidates for 2016. China’s economy, whose might acted as a counterweight to the slump in the rich world in the years after the crisis, is now itself a worry. Other emerging markets, notably Brazil, remain in a deep funk. The sell-off in the high-yield-debt market in December has prompted fears of a broader re-pricing of corporate credit this year.

Yet one worry is absent: financial markets are priced for continued low inflation or “lowflation”.

A synthetic measure, derived from bond prices, puts expected consumer-price inflation in America in five years’ time at around 1.8%. That translates into an inflation rate of around 1.3% on the price index for personal-consumption expenditure (PCE), the measure on which the Federal Reserve bases its 2% inflation target. Ten-year bond yields are just 2.3% in America, and are below 2% in Britain and below 1% in much of the rest of Europe. The price of an ounce of gold, a common hedge against inflation, has fallen to $1,070, far below its peak in 2011 of $1,900. Yet market expectations are often confounded. Economic recoveries are maturing. Labour markets are tightening. Could inflation be less subdued than expected in 2016?

Rich-world inflation is currently depressed because of temporary influences. In America the PCE index rose by just 0.4% year on year in November—but that is in large part because of a sharp fall in consumers’ energy prices in early 2015, which will soon drop out of the annual comparison. The core measure, which excludes food and energy prices, has been stable at 1.3% for months. It might also be somewhat suppressed by the sharp fall in oil prices, which has held down the cost of producing other sorts of goods and services. An analysis by Joseph Lupton of J.P. Morgan finds that core inflation worldwide has crept up to 2.3%, a rate that has rarely been exceeded in the past 15 years. In biggish emerging markets, including Brazil, Russia and Turkey, core inflation is above the central bank’s target (see chart).

A low blow

In the view of some, lowflation is a relic of the past. Even the euro zone is recovering from its prolonged recession; the business cycle in other rich economies is more advanced. The debt hangover that has troubled them for almost a decade has faded. Job markets are also a lot tighter than a few years ago, when deflation was a serious concern. Unemployment in America has fallen to 5%, a rate which is close to many estimates of full employment. The jobless rate in Britain is 5.2%. In Germany it is 6.3%. If the recent trend of low productivity growth in these economies continues, bottlenecks in the jobs market will emerge and higher inflation may not be far behind. For instance, if America’s GDP grows by 2.3% in 2016, its recent average, and growth in output per worker also matches its recent sluggish trend, the unemployment rate would decline further, to around 4%, reckons Mr. Lupton. The lower the jobless rate goes, the more likely it is that wages—and eventually inflation—will pick up.

As rich countries were wrestling to reduce their debts, emerging markets went on a credit binge for which the reckoning is just beginning. Debt in China in particular has risen sharply relative to GDP since 2008. Some of the resulting stimulus went into factories, leading to overcapacity and falling global prices for various goods, from steel to solar panels. But a lot of China’s debt went on financing housing and infrastructure, rather than its export capacity. Moreover, the Chinese authorities’ desire to avoid big lurches downwards in the yuan ought to minimize the risk that it exports lowflation to the rest of the world.

Nonetheless, the expectations projected by bond markets—that lowflation will persist—have sound underpinnings. For a start, the price of oil and other commodities does not yet seem to have reached bottom. The price of a barrel of oil fell to an 11-year low of under $36 before Christmas, before rallying a little on hopes of renewed stimulus in China. Saudi Arabia is pumping at close to capacity, in an effort to force out high-cost producers such as America’s shale-oil firms and thus grab a bigger slice of the global market. The strategy has had some success. For instance, the number of oil-rigs operating in America has fallen from around 1,500 a year ago to just 538, according to Baker Hughes, an oil-services firm. But oil production in America remains above 9m barrels a day, and Iran’s exports are likely to increase in 2016, thanks to the lifting of Western sanctions. For the time being, the oil market heavily favors buyers over sellers.

Where inflation can be found in the world, it is not obviously a function of capacity constraints. The biggish economies in which core inflation is above the central bank’s target tend to be commodity exporters that have suffered big falls in their currencies. That, in turn, has stoked domestic inflation. Core inflation is typically well below target in countries that are importers of raw materials. And despite tighter labor markets in rich countries, wages are not rising very fast. That might in part be because of low expectations of inflation.

It seems likely, also, that the debt burden in emerging markets, and the slower growth that usually comes after a credit binge, will bear down on global prices for a while. Even if China’s spare capacity is not fully exportable, plenty of other emerging markets have built mines and factories in expectation of higher Chinese growth that will now prove redundant. As nervous investors creep back to the comparative safety of developed markets, the upward pressure on big currencies, notably the dollar, will increase—adding to downward pressure on local prices.

As was the case in the late 1990s, rich-world policymakers will find that they have to keep their domestic economies primed with low interest rates to offset disinflation from abroad. The strong dollar has already caused a split in American industry between strong services and weaker manufacturing. Lopsided economies may prove as hard for policymakers to steer as deleveraging ones.

Buttonwood

Tales of the unexpected

Five potential surprises for 2016

INVESTORS often start the calendar year in a buoyant mood, only to be caught out by unexpected events. It is almost inevitable that the consensus will be proved wrong in some respects, not least because the views of most investors will already be reflected in market prices.

So this column would like to suggest five potential surprises for 2016. The definition of a surprise is something that the consensus (as judged by betting sites or polls of fund managers) does not expect.

The first surprise may be that the dollar weakens, not strengthens. The consensus view is that the Federal Reserve, having pushed up rates before Christmas, will tighten monetary policy two or three more times in 2016. Higher rates will make investors eager to buy the dollar, especially as both the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan will keep their rates near zero. However, the dollar has already had a very good run, so higher rates may already be priced into the currency. As it is, investors seem to doubt that the Fed will tighten as much as the central bank currently projects. The actual outcome may be feebler still.

The second surprise may be too familiar to deserve the name. Commentators have been calling an end to the bull market in government bonds for many years now, and the pundits are expecting much the same in 2016. But persistently low inflation and the support of central banks have kept yields low to date, and may keep doing so. It is all reminiscent of Japan: since 2000, so many investors have failed to profit from betting on higher Japanese yields that the trade is known as the “widowmaker”. In the developed world, pension funds, insurers and retired workers are all eager buyers of fixed-income assets. Perhaps bond yields will edge higher in 2016, but not by very much.

These two surprises may have a common cause: the failure of the global economy to grow as rapidly as some hope. In turn, economic sluggishness seems likely to drive voter discontent. And that may lead to the third and fourth surprises.

Third Surprise American political risk could dog the markets in late 2016. At the start of 2015, investors probably anticipated a dynastic clash between Jeb Bush and Hillary Clinton. But the Republican candidate seems more likely to be either Donald Trump or Ted Cruz. The former has argued for a ban on Muslims coming to America and a wall on the southern border; the latter’s proposals include a flat income tax, a sales tax and a monetary system linked to gold. Although Mrs. Clinton would be the favorite in a race against either man, she is a flawed candidate, mistrusted by many voters. The prospect of a Cruz or Trump presidency would lead to considerable uncertainty in the markets: should either man be elected, would they try to stick to their campaign pledges and would Congress let them? Indeed, this uncertainty might be another reason why the dollar may struggle in 2016.

Fourth surprise. Political risk might also be a problem in Britain, which is likely to hold a referendum on leaving the European Union in 2016. It is widely assumed that Britons will vote for the status quo: that outcome has a 78% probability on the PredictIt website. But opinion polls show that the “remain” and “leave” camps are almost deadlocked and the press is fairly Eurosceptic. Voters might use the referendum as a means of protesting against high levels of immigration, which the government has promised, but failed, to reduce.

If Britain votes for exit, there will be much uncertainty about the country’s attractiveness to foreign investors. Scottish voters are much more pro-EU than English ones, and Brexit would prompt calls for a second independence referendum so Scotland could stay in the single market. David Cameron, Britain’s prime minister, would surely have to resign if his referendum gamble backfired. All this might be good reason to sell the pound.

The final surprise might be more benign: emerging markets could perform rather better than investors expect. A poll of fund managers in December by Bank of America-Merrill Lynch found that pessimists on emerging markets outnumbered optimists by 27 percentage points. There is plenty of bad news: China’s slowdown, falling commodity prices and recessions in Brazil and Russia, for example. But this may have been built into prices; the MSCI emerging-market index has fallen by 20% over the past six years while the S&P 500 index is up by 40% (see chart). It may be time for a rebound.

Not all of these surprises will come to pass, of course. But it seems likely that at least one or two will. Predicting which ones may mark the difference between success and failure for investors in 2016.

Economist.com/blogs/buttonwood

An unsettling year for the markets

The outlook is exceptionally cloudy

Philip Coggan

Mon Nov 02 2015

Finance

Investors face every new year with uncertainty. But the outlook for 2016 is especially hard to fathom because of two key questions: will the slowdown in the Chinese and other emerging economies continue? And how far will the Federal Reserve (perhaps the Bank of England) move to tighten monetary policy?

The pattern in recent years has been for investors to start the year in optimistic mode about the outlook for economic growth and corporate profits, only to temper their enthusiasm over the summer. But this time is different. Moody’s, a ratings agency, has reduced its GDP-growth estimate for G20 economies in 2016 from 3.1% to 2.8%. Global trade has been disappointing: volumes fell in the first half of 2015 for the first time since 2009.

Since the financial crisis, investors have seen weak economic data as providing a good excuse for central banks to ease policy. That might be a bit much to expect from the Fed in 2016, but investors will be happy if any interest-rate increases are few and far between. The European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan still seem committed to monetary expansion. But the big hope is that China will respond to its slowdown with some policy stimulus, a move that would give a big fillip to other emerging markets, particularly commodity producers.

Equity markets in the developed world have benefited from low interest rates (which have steered investors out of cash and into risky assets) and from healthy profit margins, thanks to subdued wage pressure. But with American unemployment having fallen significantly, real wages are rising because of subdued inflation. And slowing emerging markets mean that companies cannot count on a bounce in global demand to keep profits motoring.

The waiting game

Bond investors must feel as though they are in a state of suspended animation. Every year, most commentators predict that the era of low yields is bound to end, because of a pick-up in growth and inflation, or a change in monetary policy. But the big sell-off has never really occurred; in 2015 quite a few European government-bond markets even had negative yields for a while. The default rate on corporate bonds remains low by historical standards and companies have managed to lock in low rates, easing the strain on their finances. Until inflation surges again, it is hard to see why bonds should sell off, and falling commodity prices and weak growth mean global inflation is likely to stay subdued. (Poorly run countries like Russia and Venezuela are exceptions.)

For commodities, the news has been so bad that the mood must change at some point. Investors have become convinced that the “supercycle” is in the down phase; abundant supply is overwhelming stagnant demand. Oil is the obvious example: Saudi Arabia’s attempt to put American frackers out of business in 2015 didn’t seem to work, and in 2016 production from post-sanctions Iran will be hitting the market. However, a lot of bad news may now be priced in.

Economic and profit fundamentals are not, of course, the only factors that could affect investment decisions in 2016; politics may come into play. The Greek crisis rattled markets for months in 2015. The big political event of 2016 will be the American presidential election. Investors will be sanguine about the outcome of a Bush-Clinton contest but will get nervous if the alternatives are Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump. British investors will get twitchy in anticipation of the country’s referendum on EU membership

The final cause of uncertainty may be market liquidity. For regulatory reasons, banks are no longer playing as big a role in market-making as they used to. The sell-off in August 2015 indicated that prices can crater for a while, with investors unwilling to hunt for bargains. The occasional “flash crash” is one thing; if they happen every month, investors might start to find zero returns on cash more attractive than before.

Philip Coggan

Buttonwood columnist, The Economist

Economic milestones of the year ahead

Jan 1st 2016, 13:46 by The Data Team

A NUMBER of economic trends that have been simmering for years will come to full boil in 2016—and result in some striking statistics. One example is in wealth inequality. The share of wealth of the richest 1% of the world’s population will, according to Oxfam, exceed that of the remaining 99% of people. Yet there is also some good news for ordinary folk: in at least one respect private investing is becoming more democratic. The amount of global crowdfunding investment is expected to reach $34 billion in 2015, and in 2016 will surpass the annual money committed by investors to venture-capital funds globally.

GDP forecasts

The fastest shrinking and growing economies in 2016

WORLD GDP is forecast to grow by 2.7% in 2016, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit (in 2015 the economy is estimated to have expanded by 2.4%). This moderate outlook reflects the fact growth is still lack-lustre in the euro area, Japan and emerging market economies as a whole.

The picture is particularly gloomy for commodity-exporting nations such as Venezuela, which is in deep economic recession. The outlook for Brazil is far from positive too, where falling oil prices combined with the implications of the Petrobras scandal will affect investment in oil and gas. War-torn countries also feature in the projected worst performers of 2016. Libya’s GDP has been contracting since 2013; continued conflict and political uncertainty means that it will continue to shrink this year.

There are a few bright spots however. Although GDP growth in Turkmenistan is slowing, the construction of a new branch of the Central Asia-China gas pipeline should help to support exports. A scattering of emerging Asian countries make a notable appearance in the top-ten: growth in the region is buoyed by rising private consumption, and in particular a revitalized tourism sector in Laos.

Asia-Pacific Report: China has challenges ahead to make economy more efficient

By Chuck Chiang, Vancouver Sun January 3, 2016

Stock market instability was a major economic news story in China this past year.

For much of the past decade, a good portion of global trade and investment — and arguably the majority of trade in the Asia-Pacific — centred on the rapid growth of China’s economy, now the world’s second-largest.

With the stock market upheavals, currency fluctuations and moderating growth indicators in 2015, however, there are signs that the Chinese economy may be entering a “new normal” for 2016.

What changes are coming? Economies like Canada, whose exports to China reached $18.9 billion this year while imports hit $58.7 billion, are keeping a close eye.

In an analysis published by crowdsourcing consultancy Wikistrat , Asia Pacific Foundation senior fellow and seasoned Canadian ex-diplomat Hugh Stephens argues that Beijing’s economic challenges will likely mean further structural reforms in the way it attracts investment, as well as dealing with the performance of state-owned enterprises in the global market.

Stephens, a 35-year veteran in global trade and business management affairs, said some of Beijing’s reforms in the coming year may be unexpected, but are necessary to boost the country’s economy as targeted annual growth rests at 6.5 per cent for 2016, significantly lower than years past when double-digit figures where the norm. The efficiency of state-owned enterprises, he said, will likely be front and centre.

“The track record of Chinese overseas investment through state-owned enterprises has been less than stellar,” Stephens said. “Bad bets have been taken on a number of investments, (return on investment) has been disappointing, and corruption charges have been pursued against a number of senior state-owned enterprise executives.”

Canadians are most familiar with Chinese state businesses such as energy giant CNOOC, which paid $15.1 billion for Calgary-based Nexen in 2012 (in a deal that prompted Ottawa to close the door on controlling interest in Alberta’s oil sands projects to Chinese companies).

While the current slump in crude prices is the main culprit, Nexen has underperformed since becoming part of CNOOC’s portfolio. A Wall Street Journal report in July noted its Long Lake oil sands operation’s production reached 50,000 barrels per day, about 22,000 barrels below the planned capacity.

Stephens argued that Beijing should look to imbue its state-owned enterprises with more say in how it should operate, rather than reining them in, in order to have them succeed globally.

“China could do more of the same in terms of retrenchment/hunkering down and trying to clean up management,” he said. “Alternately, it can follow words with action and release the grip of the state on (these companies) and allow them greater flexibility to operate more like private companies, making market-based risk assessments rather than being ultimately governed by political considerations.”

Stephens also thinks China will pursue bilateral investment treaties with the United States and Europe. An investment protection agreement between Canada and China went into effect in late 2014, and similar deals with the U.S. and the EU will nudge China toward “eventual readiness to take on (Trans-Pacific Partnership)-type obligations in the future.”

It would also send a signal that Beijing, Stephens said, is ready to move toward “a more market-oriented economy” that would help China transition through its current slowdown.

chchiang@postmedia.com

© Copyright (c) The Vancouver Sun

Liberal economists

Three wise men

Wu Jinglian (left), Mao Yushi (center), Li Yining (right)

Ageing reformists diagnose the economy’s ills

Jan 9th 2016 | SHANGHAI | From the print edition

WHATEVER image you may have of the reformists hoping to shake up China’s creaking economic system, it is probably not one of octogenarians who fiddle with their hearing aids and take afternoon naps. But that is a fair description of three of the country’s loudest voices for change: Mr. Market, Mr. Shareholding and the most radical of all, the liberal. With growth slowing, the stock market once again in trouble and financial risks looking more ominous, their diagnoses of the economy, born of decades of experience, are sobering.

Wu Jinglian, Li Yining and Mao Yushi—their real names—were born within two years of each other in 1929 and 1930 in Nanjing, then China’s capital. Whether it was that or pure coincidence, all three grew up to demand an end to Soviet-style central planning and to propose, to varying degrees, capitalism in its place. Their influence has waned with age, but their powers of analysis remain sharp. And they do not much like what they see.

Mr. Wu is in some ways the most important of the group. He advised the government from the earliest years of China’s “reform and opening” in the 1980s, through the 1990s when the great China boom got under way (see timeline). He proposed that the Communist Party should declare China a “socialist market economy”, a twist of words (and a hugely controversial one—conservatives abhorred any positive mention of markets) that opened the door to private enterprise.

But Mr. Market, as he came to be called, thinks this kind of linguistic ruse has outlived its usefulness. Imprecise concepts have led to flawed actions, he warns. Though the private sector has flourished over the past couple of decades, the state still looms large, controlling financial flows and acting as gatekeeper for virtually all important decisions, from land deals to mergers. “Even a low-level bureaucrat can decide the life or death of a company. You need to listen to the party,” says Mr Wu, who now teaches at the China Europe International Business School in Beijing.

Mr. Wu notes contradictions in the official blueprint for reforming state-owned firms. The party promises to empower their boards, but still wants to retain authority over the appointment of top executives. “If you can’t solve this problem, it will be very difficult to develop effective corporate governance,” he says. Mr. Wu argues that political change is now needed to shore up the economy: the government must stop meddling in markets and instead focus on developing the rule of law. Holding up a copy of his recent book, he chuckles softly. “All my ideas are in here. No one pays them much attention.”

Getting heard is less of a problem these days for Li Yining, who has spent his entire academic career at Peking University. His former pupils include Li Keqiang, China’s prime minister. His big idea in the 1980s was that selling partial stakes in state-owned companies to the public would improve their performance—hence his nickname, Mr. Shareholding. The party eventually took his advice, though the companies remain hugely inefficient.

In diagnosing the problems of today, Li Yining is blunt: the previous few years of ultra-high-speed growth “did not accord with economic laws”. China wasted natural resources, damaged its environment, piled up excess capacity and missed opportunities to fix its economic model. Yet perhaps because of his connections to those in power, Mr. Li is by far the most sanguine of the old guard of reformers. “The new normal”—President Xi Jinping’s favorite economic slogan—is shifting the economy in the right direction, by aiming for lower growth and structural changes.

China’s growth is slowing. A detailed look at what is behind the slowdown

Mao Yushi disagrees. And unlike many economists cowed by a frostier political climate, he is unafraid to say so. Mr. Mao started his career in the railway system, including a spell driving trains, before retraining as an economist in the 1970s. Always on the margins of Chinese academia, he founded the Beijing-based Unirule Institute of Economics in 1993, an independent think-tank. He champions deregulation and courts controversy in his criticism of Mao Zedong’s disastrous rule. Some diehard Maoists call the softly spoken economist “Mao Yu-shit” online, playing on a homonym of his name.

In Mr. Mao’s view it is already too late for the economy. China has too many empty homes and its banks have too much bad debt. “A crisis cannot be averted,” he says. Mr. Mao allows himself some optimism, however. The young generation is educated and open-minded. The waste of capital and resources of recent years implies that China still has good potential for growth, if it can operate more efficiently. But he believes that Mr. Xi, while espousing reform, is strengthening the state’s economic grip. “He has the power and the determination to fix problems, but in many cases he does not properly understand the problems,” says Mr. Mao.

Such unvarnished, open criticism of Mr. Xi is rare in China these days. Speaking in the living room of his apartment, its walls stacked high with books and yellowing newspapers, Mr. Mao says that his age and experience give him, and the other elderly reformists, a bit of leeway. “If it was someone else speaking, they would probably be arrested. But to me, the government is polite.” If only it would pay more heed to the elders’ advice, too.

Track global exchange rates over time with The Economist’s Big Mac currency index

MIGHT “Made in Russia” labels become common? If currency depreciation alone could boost exports, then yes. According to our latest Big Mac index, the Russian rouble is one of the cheapest currencies around, 69% undervalued against the dollar. The index compares the cost of the famous burger at McDonalds outlets in different countries by converting local prices into dollars using market exchange rates (as of January 6th). It is based on the idea that in the long-run, exchange rates ought to adjust so that one dollar buys the same amount everywhere. If a burger looks like a bargain in one currency, that currency could be undervalued.

These large currency devaluations can hurt, by raising the price of imports and spurring inflation. But although devaluations may not be pleasant, they are meant to be nutritious. Pricier imports should encourage consumers to switch towards domestic products and stimulate local production. A cheaper currency should also boost growth by spurring exports.

Between 1980 and 2014, according to an analysis of 60 economies by the IMF, a 10% depreciation relative to the currencies of trading partners boosted net exports by 1.5% of GDP over the long term, on average. Most of the improvement came within the first year.

But devaluations do not seem to have provided quite the same boost recently. Japan is the best example. The yen has been depreciating rapidly. A Big Mac was 20% cheaper in Japan than in America in 2013; now it is 37% cheaper. Yet export volumes have barely budged. This is a surprise: the IMF calculates that Japanese exports are around 20% lower than it would have expected, given how the yen has weakened. Devaluations in other countries, including South Africa and Turkey, have also disappointed.

A global contraction of trade in dollar terms may be obscuring devaluation’s benefits. Although exports from countries with weakening currencies may look limp, many of them are still securing a bigger slice of the shrinking pie. The collapse in commodity prices is also masking some signs of life. Take Brazil, where the volume of exports rose by 10% in 2015 even as their value plunged by 22%. Some of that is caused by commodity exporters compensating for falling revenue by selling ever more minerals and oil. But not all of it. In Australia, for instance, exports of goods other than raw materials jumped by around 6% in mid-2015, according to the Commonwealth Bank of Australia.

But there are also signs that “Dutch disease” has taken a toll on the capacity of commodity-producing countries to ramp up other exports. When prices were high, capital flowed in, pushing up their currencies and thus making their other exports less competitive. Labour and investment flowed mainly to commodity firms. That has left other industries too weak to pick up the slack now that these once-soaring currencies have fallen back to earth.

Russia is a good example. Non-energy exporters appear to be struggling despite the rouble’s plunge. Over the first half of 2015, as the volume of energy exports surged, non-energy exports fell, according to Birgit Hansl of the World Bank. She points out that it is not enough to have a price change: “First you have to produce something that someone wants to buy.” The ruble’s weakness is an opportunity for industries that already export, such as chemicals and fertiliser. But boosting other exports requires investment in new production, which takes time.

Both the IMF and the World Bank have highlighted another possible explanation for the weak performance of exports in countries with falling currencies: the prevalence of global supply chains. Globalization has turned lots of countries into way-stations in the manufacture of individual products. Components are imported, augmented and re-exported. This means that much of what a country gains through a devaluation in terms of the competitiveness of its exports, it loses through pricier imports. The IMF thinks this accounts for much of the sluggishness of Japan’s exports; the World Bank argues that it explains about 40% of the diminished impact of devaluations globally. That leaves many manufacturing economies in a pickle.

VIETNAM

Vietnam’s wood industry is expected to gain a total export value of wood and wooden products of US$7.7 billion for this year, higher than $7.1 billion in 2015. According to the Vietnam Wood and Forestry Products Association (Viforest), exports of wood and forestry products from Vietnam will have the advantage of starting operations through the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) and the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) deal.

Local enterprises have done good business with ASEAN partners for many years so the AEC will create favourable conditions for them to develop further business incoming time.

Meanwhile, TPP will also usher in opportunities for the domestic wooden product makers to have more legal wooden material for export processing because the TPP member countries have great potential for high quality wooden materials with legal origins, according to Nguyen Ton Quyen, chairman of Viforest.

That will create more opportunities for Vietnamese manufacturers to export their products to the European Union (EU) and the United States (US) where there is a high demand for licensed wooden products.

In 2015, Vietnam achieved total export value of wooden and forestry products at $7.1 billion, 8 per ent higher than 2014, according to the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development.

The three largest export markets of Vietnamese wooden products are the US, Japan and China, accounting for 67 per cent of the total export value.

Last year, there were many export markets of Vietnamese wooden products with high export value such as India with a growth rate at 64.45 per cent, Hong Kong with rate at 41.95 per cent, the US at 17.8 per cent and Germany at 10 per cent.

Quyen said the export value increase was due to high demand in the world market in 2015, the Thoi bao Kinh doanh newspaper reported.

For instance, the US market needs to import wooden products worth $27 billion per year while Vietnam exported wooden products between $1 billion and $2 billion per year. The EU market has a demand for wooden products worth $85 billion but Viet Nam’s export value to the EU reaches only between $700 million and $800 million per year.

Moreover, Vietnam’s wooden products had high competitive ability and a reputation on the world market. Therefore, Vietnamese enterprises would have numerous opportunities to export their wooden products to those markets, he said.

Fordaq

7 things that could go horribly wrong in 2016: Don Pittis

Forewarned is forearmed as we take a gloomy look around the world

By Don Pittis, CBC News Posted: Dec 31, 2015 5:00 AM ET Last Updated: Dec 31, 2015 1:24 PM ET

A beggar kneels in front of an advertising billboard in the centre of Vienna in November. If world economies weaken in 2016 it will become harder to narrow the gap between rich and poor. (Reuters)

Earlier during this holiday season I offered an optimistic view for the coming year that we would be possessed by animal spirits, making 2016 a boom year for growth and exports.

But a scan of financial stories looking to the year ahead shows there is a lot of pessimism out there as well. Here is a selection of some of the gloomier predictions of what could go wrong with the economy.

1. China crash

A perennial cause for worry, China’s economy has been so strong for so long, there always seem to be perfectly good reasons why everything could go terribly wrong.

In 2015 there were many new warnings, but an especially strong one from the Jim Cramer organ TheStreet.com says the middle kingdom faces a “sudden stop” in its economy.

A failing currency, a shrinking real economy, a real estate bubble, industrial overcapacity, say the worriers, all mean the Year of the Fire Monkey in the Chinese zodiac could spell doom for what is by some measures the world’s largest economy.

2. Emerging-market bankruptcy

International Monetary Fund boss Christine Lagarde has been warning for months what would happen to an unstable developing world if the U.S. began raising rates.

Convinced by global hype that BRIC countries were the future, companies and countries over-borrowed, leaving many with a giant hangover.

The Economist magazine says Brazil faces “political and economic disaster,” Russia has been hammered by falling oil prices, and China worries are mentioned above. That leaves India as the final BRIC success story. Can it last?

3. Oil to $20

There are few better indicators of global overcapacity than cheap oil.

But rather that scaling back on output, there are worries that new production from Iran could increase the glut just as a slumping developing-world economy cuts demand. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia is cutting back on expenditures, saying it will pump cheap crude till other world producers cry uncle.

New York bankers Goldman Sachs say oil could fall below $20 a barrel in 2016.

4. Markets melt down

If oil and commodities continue their plunge in 2016, low prices could eventually cause serious damage to oil producers and mining companies that can’t be solved by layoffs.

There are distinct worries that the troubles of resource companies could be passed on to banks. Junk bonds and ETF markets are also a source of concern.

Janet Yellen, chair of the U.S. Federal Reserve, looks toward Thomas Perez, U.S. secretary of labor. Yellen has warned there is a 10 per cent chance of an economic shock that could drive the U.S. recovery off course. (Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg)

Any one of those things could represent the “10 per cent chance” of an unexpected economic shock that U.S. Federal Reserve chair Janet Yellen warned about in her last policy presentation.

5. Escalating global conflict

This is obviously not just an economic concern. In fact, an escalation of hot war could be an instant solution to the commodities glut.

As usual, the most frightening danger could come from an overwrought, unstable leadership such as those in North Korea or Pakistan popping a nuke at a hated enemy.

But according to The Atlantic Magazine, there are plenty of chances for expanding conflict. And that list only includes those that would directly affect the United States.

6. Canadian property crash

Other evergreen sources of doom and gloom in the Canadian economy are the overheated property market and record levels of consumer borrowing.

This week even the Globe and Mail, which is usually reluctant to be gloomy about real estate, warned that Canadian property may have “finally met its Waterloo” in 2016.

A combination of tighter mortgage rules, rising U.S. interest rates and crashing resource prices may conspire to slow the Canadian real estate rocket.

The question remains: Can, as optimists hope, the rocket stop and hover at the top of its trajectory, or must it reverse course?

7. U.S. failed takeoff

One of the only true bright spots in the global economy is a steady recovery in the U.S. In her most recent media outing Yellen said the U.S. domestic economy was on the upswing despite sagging exports.

But with everyone else from Europe to China to Brazil to Canada running on slow, can the U.S. pull itself up by its bootstraps? That may be difficult, especially when its currency is surging to new highs.

Without growth, the global spread between rich and poor will likely worsen. Continued U.S. weakness might be a short-term palliative for Canadian property prices, but without America to pull us all out of the long-term morass, we are more likely to stay there.

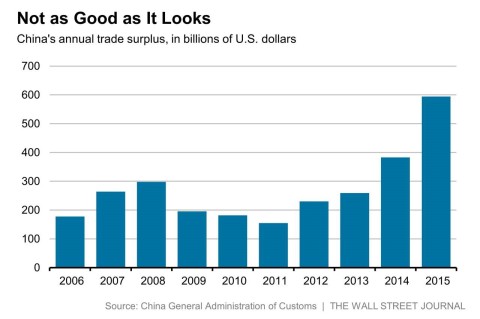

Why China’s Hefty Trade Surplus Is Dwarfed by Outflows

No wonder the yuan is under pressure: It appears capital outflow in 2015 came to around $750 billion

Aaron Back

The Wall Street Journal

Updated Jan. 13, 2016 12:15 a.m. ET

China’s fat trade surplus should be a source of comfort. But juxtaposed against falling reserves, it actually sends an alarming message about the degree of capital flight.

The surplus swelled by 55% in 2015, to $595 billion, figures released Wednesday showed. This news isn’t as good as looks. For one, it doesn’t reflect a boom in exports, which for the full year actually fell by 2.8%. The surplus widened because imports fell even more, by 14.1%.

Moreover, it raises a question: How did China manage to post a decline of $513 billion in foreign-exchange reserves last year? Since a trade surplus brings foreign currency into the country, and most exporters turn that currency over to the central bank, it should boost reserves by a corresponding amount. That reserves fell suggests fund outflows large enough to overwhelm even that trade surplus.

To get a full picture, more variables must be accounted for. Full-year data isn’t yet available for China’s foreign direct investment, overseas direct investment and services trade deficit. But based on numbers currently available, and adding the trade surplus, a rough estimate of total net inflows from trade and direct investment in 2015 comes to about $379 billion.

There’s a dark side to the trade surplus. Photo: china daily/Reuters

This must be compared with the fall in reserves. In fairness, this decline was exaggerated by the stronger dollar, which makes China’s holdings in other currencies less valuable when they are reported in dollar terms. Taking these valuation effects into account, and based on estimates of the composition of its mostly secret portfolio, China may have sold a net $375 billion of reserves in 2015.

Putting these two figures together, it appears that there was roughly $750 billion of capital outflow in 2015. No wonder the currency is under pressure.

Write to Aaron Back at aaron.back@wsj.com

9:22 pm ET

Jan 12, 2016

Will the Pacific Trade Pact Really Put Pressure on China?

• By William Mauldin

Container trucks leave the Port of Shanghai in August.

A recent World Bank study says China would see a tiny increase in trade and a “really negligible” reduction in GDP by 2030 due to its exclusion from the Pacific trade deal. JOHANNES EISELE/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

President Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Sen. Rand Paul don’t agree on much.

So it’s not a surprise that each is espousing totally different views on how a big Pacific trading agreement will affect China, which is not a member of the trade bloc. And as it turns out, each can claim support from experts and economists.

Mr. Obama on Tuesday told members of Congress they should vote for the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement because it will ensure that Washington’s commercial rules of the road become the norm in the Pacific, rather than China’s. “With TPP, China doesn’t set the rules in that region—we do,” Mr. Obama said in the State of the Union address, revisiting an argument he aired during his 2015 address, before the TPP was concluded in October.

The 12 nations agreed to a deal that, if implemented, would not only reduce or eliminate tariffs but rein in the advantages of state-owned enterprises and impose binding environmental standards.

Even though Beijing isn’t part of the deal, Obama administration officials say the rules will still challenge China to reform its economy in other ways. The TPP, endorsed by many former military officers, would also boost Washington’s ties with its allies in the region a time when China is flexing its economic and military muscles.

Mr. Trump disagrees. “It’s a deal that was designed for China to come in, as they always do, through the back door and totally take advantage of everyone,” the billionaire GOP candidate said at the fourth GOP presidential debate, in November.

Mr. Trump’s warning echoes criticism from labor unions and Democrats from auto-producing states in the Midwest. They point to the “rules of origin” in the TPP that allow much of the content of cars and other products traded duty-free to come from outside the bloc—including China.

This week Public Citizen, a consumer-watchdog group, poked fun at the Obamas for inviting an American honey producer to attend Tuesday’s speech as a symbol of how the TPP can open up markets like Japan through lower tariffs. In trade circles, “honey laundering” is a symbol of how some imported Chinese products avoid U.S. tariffs by shipping through a third country, such as Malaysia—a TPP member.

Still, some politicians, such as Mr. Paul, seem to think all the talk about China misses the point. “You know, we might want to point out China is not part of this deal,” Mr. Paul said in a pointed response to Mr. Trump during the November debate. The Kentucky senator opposed legislation designed to expedite the TPP because he believes Congress, rather than the Obama administration, should be designing trade policy, whether it’s with China, Japan or the European Union.

Some economists are also saying the talk of China is overblown. A study published by the World Bank last week says China would see a tiny increase in trade and a “really

2016: Why India Is the World’s Fastest-Growing Economy

1/13/2016 7:02AM

According to the World Bank’s latest forecasts, India will be the world’s fastest growing economy in 2016, as China slows. Here’s why. Photo: Associated Press

Liquidity fears in indexed products have caused jitters this year

The next financial crisis will be played out in indexes and exchange traded funds. That is inevitable given the huge share that ETFs now take of investor fund flows, and their popularity as hedge fund trading vehicles.

What is less clear, and deeply controversial, is whether the structure of ETFs will itself contribute to the next crisis, or even cause it. Regulators, worried by past incidents when untested financial innovations helped exacerbate financial crises, are worried that it could.

ETF providers indignantly counter that they make the market more liquid, and less prone to sudden stops. Indeed, they complain that well-intentioned regulations exacerbate a problem they were meant to cure.

The scale of the ETF industry is not in question. They now hold more than $3tn in assets. But this raises the question of whether they have come to lead the market rather than follow it. This operates at two levels. First, there is a concern that the power of the indexes distorts markets over time, and second, there is the possibility that the structure of ETFs and index funds worsens market shocks when they happen.

Indexes’ influence spreads to virtually all institutionally managed funds. Benchmarking by the consultants on whom institutions rely when choosing fund managers is so widespread, that active managers have no choice but to watch the index they are compared to very closely, and are obliged to follow any major changes in its composition.

Examples are easy to come by. When the Russell indices — highly popular among US fund managers — are updated each year, they often drive the heaviest trading of the year. In June this year, Chinese A-shares peaked and began to fall shortly after MSCI, the most important index provider for emerging markets, decided to delay including them in its flagship index. This came as a surprise. Showing the importance of indexers, Chinese authorities had lobbied hard for inclusion, as this would have driven capital into the A-shares market. Many investors at the time said that the subsequent sell-off could in part be attributed to the knock to confidence that came with MSCI’s decision.

Indexers do their best to limit their impact on the market. Russell makes its methodology very public, so investors can see weeks in advance what changes are likely to its indices. MSCI conducts public consultations.

But while indexing and benchmarking remain so prevalent, the problem of overpowerful indexes seems impossible to avoid. It can merely be mitigated. For passive investors, rules for indexes must remain as clear as possible. For active managers, the solution may be to change benchmarking.

Rather than looking at past performance, which does not predict the future, consultants could look at investors’ past behaviour, or rate them on their degree of style discipline. If clients show that they are more interested in highly concentrated funds taking contrarian positions, and not in funds that merely shadow an index, then the industry would adjust to meet the demand, and the systemic problems caused by indexes should reduce.

Then there is the issue of market structure. Two incidents in 2015 raised concern. First, there was August 24, when US share prices gapped downwards at the opening in New York, and ETF prices were not available for a while. Second, in December, a gradual sell-off in high-yield bonds turned into a rout for ETFs holding high-yield bonds.

FT series Market Shocks 2015

Investors experienced plenty of shocks during 2015, the FT looks at the highs and lows including currencies, emerging markets, bonds, equities and commodities

Was this due to liquidity mismatches? It is a fair question. ETFs only offer prices throughout the trading day because market makers trade to ensure that there is no gap between the market price and the underlying price of the securities in the index they track, so this has to be a risk — especially when, as in the case of high-yield bonds, the underlying security is fundamentally less liquid.

There are two theories. One, held by the industry, is that the problems were driven if anything by regulations. Mandatory trading pauses following the 2010 “flash crash” made it harder for ETF managers to get a handle on the underlying price of their securities, and created problems. The other theory: there is indeed a mismatch.

Debate is healthy. The echoes of credit derivatives, which in 2008 helped to turn a serious housing downturn into a near-collapse of the world financial system, are clear enough. Without a major market disruption — and 2015’s turbulence barely ranks compared with the events of 2008 — it is hard to test whether new financial instruments will work as intended when under stress. Better for everyone, including ETF providers, to err on the side of caution.

If it’s the economy, stupid, what can be done?

By Harlan Ullman, Arnaud de Borchgrave Distinguished Columnist | Jan. 18, 2016 at 6:00 AM

A big decline in China’s stock markets is affecting global markets. Photo by Stephen Shaver/UPI

If the first 10 days of the New Year are indicative of the economic outlook for 2016, buckle up.

The precipitous decline in China’s stock markets has had dramatic financial and economic effect on global markets. The drop in oil prices to above $30 a barrel earlier this week will bring further turmoil.

So are we seeing the beginning of a global recession possibly as crippling as the 2008 financial meltdown was? Or is this merely a readjustment magnified by China’s economic troubles that will settle out? Strong arguments can be mounted on both sides.

Regarding a recession, here is why global economies may be headed for rough times. The shift in demand and consumption from the developed economies to the BRIC’s — Brazil, Russia, India and China — and emerging markets is considerable, and now accounts for more than 55 percent of the global total, with three of the BRIC in some form of potentially grave economic difficulty.

China’s real estate and market bubbles may burst. As consumer demand decreases, so, too, does Chinese appetite for imports, causing a global slowdown. Currencies are affected. Because of globalization, keeping this malaise from spreading may be impossible. Likewise the decline in the price of oil is doing great damage to the energy industry and obviously the foreign currency reserves of the energy-producing states.

To the degree that price-to-earnings ratios matter, in the United States historically, they averaged 14 -16/1. Today, P/E’s are running much higher, suggesting that stocks are overpriced. Hence, a market adjustment may be greatly accelerated by any economic slowdowns. The conclusion is a very bearish outlook.

Making the opposite case, in the United States, unemployment is running at about 5 percent. Job creation continues at a rapid pace. The economy is still growing, although modestly. Automotive sales set a record last year of more than 17 million. Interest rates remain low, and corporate profits appear sound.

In this analysis, declines in share prices will produce opportunities that can rejuvenate the bourses and stock exchanges, particularly in America where fixed income investments, i.e. bonds, still have relatively low yields in exchange for providing more security for the holders. Besides, over the long term and through depressions and recessions, equities markets ultimately grow and over time provide the larger returns on investment.

But who really knows? Economies and markets evolve, and past experience and history may or may not be relevant. The great 1987 stock market collapse; the bursting of the dot.com bubble in the late 1990s; and the 2007-08 financial crises stemmed from different causes and were resolved by different means, including the passage of time.

For those who regard a recession as the most likely outcome this year, given that monetary policy, i.e. interest rates, offers little positive leverage, fiscal policy, i.e. budgets, greater deficit spending is the way out. This Keynesean approach will increase the national debt that is about 100 percent of annual GDP approaching $20 trillion. However, so this argument goes, as the economy improves, so, too, will the revenue tax base ultimately allowing reducing debt and deficit?

Those who are more bullish are likely to argue that tax cuts and changes on the margin will be sufficient, as the economy is still sound. Time will settle this debate. But common sense argues that it may not be wise to wait. What to do is the issue.

How can the economy be stimulated without increasing the debt, which both deficit spending and tax cuts will do? The answer is remarkably simple: U.S. corporations hold about $1 trillion to $2 trillion in cash outside the United States. That money can be repatriated if there is a valid mechanism.

I have long argued for a national infrastructure bank, including in my latest book, A Handful of Bullets—How the Murder of Archduke Franz Ferdinand Still Menaces the Peace. The nation’s infrastructure is in dire disrepair. These repatriated funds, if invested in this bank, would receive tax relief. The bank would be open to other investors as war bonds once were. Interest payments over, say 30 years of 200 or 250 basis points above prime, would be guaranteed by the federal government and paid for along with the principal from tolls, user fees and the like from these infrastructure projects.

Some $1 trillion or $2 trillion would surely stimulate the economy. Whether that prevents or relieves a recession is moot. However, repair of the infrastructure would, at the least, set this country on a powerful economic footing for the 21st century.

_________________________________________________________________

Harlan Ullman is UPI’s Arnaud de Borchgrave Distinguished Columnist; chairman of the Killowen Group that advises leaders of government and business; and senior adviser at Washington, D.C.’s, Atlantic Council and Business Executives for National Security. His latest book is “A Handful of Bullets: How the Murder of Archduke Franz Ferdinand Still Menaces the Peace.”

TAIWAN

Is the bubble in this property market set to pop?

Lam Yik Fei | Bloomberg | Getty Images

Leslie Shaffer | @LeslieShaffer1

Thursday, 4 Jun 2015 | 7:11 PM ETCNBC.com

SHARES

Taiwan’s long-bubbly property prices appear headed for a correction, but it doesn’t look like bargain hunters will fill the breach.

“Quite a number of buyers want to sell…(and) speculators have left the market already,” said Cliff So, executive director at REPro Knight Frank, a property agency in Taiwan.

It’s quite a shift for what had become one of the world’s frothier property markets, with prices there nearly doubling since 2009. The capital of Taipei has some of the world’s least affordable housing, with home prices at around 15 times income, according to last year’s data.

That compares with Hong Kong’s median price-to-income multiple of 17.0, Sydney’s 9.8 and Tokyo’s average 4.9, according to Demographia’s housing affordability survey of 2014 data.

Read More While HK mulls limits, Taiwan welcomes China tourists

Taiwan’s government hasn’t taken the price increases lightly, introducing a series of cooling measures. The next step on deck is the one that’s shaken out many investors in the market: a new capital gains tax is targeted for 2016, with sellers taxed based on the market price instead of a government-assessed valuation, which is usually lower.

“Taiwan’s property market has cooled in the past year,” Emily Dabbs, an economist at Moody’s Analytics, said via email. “Unfortunately, buying a home remains unaffordable for most young Taiwanese, a situation we don’t expect to change in the medium term.”

Price rises and the numbers of transactions are showing signs of a slowdown, but that may not be enough to entice the average homebuyer. Taipei house prices still rose 1.2 percent on-year in the first quarter, but that’s down from double-digit gains a year ago, Dabbs said in a May note.

But the country’s transaction value for housing fell more than 20 percent in 2014, according to data from Sinyi Realty reported by The China Post.

“The demand is still very strong. There’s not a match for the type of property,” So said, noting that over the past couple years, developers have focused on large units of over 4,000 square feet. “For a small family, that’s too much for them.”

Investors are even having trouble leasing out those luxury units, So said, adding that he expects sharp price drops in that end of the market.

Indeed, REPro Knight Frank is launching a residential property agency in Taiwan, but that’s in large part to help local property investors look overseas instead.

Taiwanese buyers have increasingly been looking outside their home market, buying around $1.63 billion worth of overseas properties in 2014, up 25 percent from the previous year.

—By CNBC.Com’s Leslie Shaffer; Follow her on Twitter @LeslieShaffer1

A Tsai is just a Tsai

The election of an independence-leaning president would put Taiwan back in the international spotlight

Jan 9th 2016 | TAIPEI |

UNDETERRED by the rain, the crowd leaps to its feet shouting “We’re going to win” in Taiwanese as their presidential candidate, Tsai Ing-wen, begins her stump speech. Some rattle piggy banks to show that their party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), relies on, and serves, the little guy—as opposed to the ruling Kuomintang (KMT), backed by businesses and fat cats and one of the world’s richest political institutions. Taiwan’s voters go to the polls on January 16th in what is likely to prove a momentous election both for the domestic politics on the island and for its relations with the Communist government in China that claims sovereignty over it. Eight years of uneasy truce across the Taiwan Strait are coming to an end.

Since taking office in 2008, the outgoing president, Ma Ying-jeou, has engineered the deepest rapprochement between Taiwan and China ever seen, signing an unprecedented 23 pacts with the mainland, including a partial free-trade agreement. It culminated in an unprecedented meeting in November between Mr Ma and Xi Jinping, China’s president, in Singapore. But if the rapprochement under Mr Ma was a test of whether closer ties would help China’s long-term goal of peaceful unification, it failed. For the past six months Ms Tsai, whose party leans towards formal independence for Taiwan, has been miles ahead in the polls, with the support of 40-45% of voters.

The KMT’s Eric Chu has 20-25% and another candidate, James Soong, a former KMT heavyweight, about 15%. Taiwanese polls can be unreliable, and many voters are undecided. But if Mr Chu were to win, it would be a shock.

Taiwan elects its parliament, the Legislative Yuan, on the same day. That race is closer. But the DPP’s secretary-general, Joseph Wu, thinks his party can win it too, either outright or in coalition with two smaller parties—and the polls suggest he may be right. If so, it would be the first time any party other than the KMT has controlled the country’s legislature since the KMT fled to the island at the end of the Chinese civil war in 1949.

The election result will have regional consequences, but the campaign itself is being fought on livelihood issues. The economy appears to have grown by only 1% in 2015, less than in 2014. Taiwan is doing worse than other export-oriented Asian economies such as South Korea. Salaries are stagnant, youth unemployment is up and home ownership is beyond the reach of many. One study found that the capital, Taipei, has become one of the world’s costliest cities relative to income, with the ratio of median house prices to median household income rising from 8.9 in 2005 to 15.7 in 2014—nearly twice the level of London. Concerns like these have dented the KMT’s reputation for economic competence.

Self-inflicted wounds have not helped either. Most of the KMT’s bigwigs refused to run for president, fearing defeat. So its chairman, Eric Chu, put forward Hung Hsiu-chu, whose pro-China views proved so extreme that they nearly split the party. Mr. Chu ditched her just months before the poll and ran for president himself. Ms. Hung’s backers, many of them old-guard KMT voters, may abstain in protest. The party which for decades has dominated politics faces humiliation.

That would have profound implications for China. For years, the Chinese Communist Party’s policy towards Taiwan has been based on patience and economic integration. But the election campaign suggests that integration is a liability and that time may not be on China’s side. In 1992, according to the Election Studies Centre at National Chengchi University in Taipei, 18% of respondents identified themselves as Taiwanese only. A further 46% thought of themselves as both Taiwanese and Chinese. Today 59% call themselves Taiwanese, while 34% identify as both—ie, very few consider themselves Chinese first and foremost.

Patience doesn’t pay

Among 20- to 29-year-olds, three-quarters think of themselves as Taiwanese. For them China is a foreign country, and the political ripples of this change are now being felt. In early 2014 students occupied parliament for three weeks in a protest against a proposed services deal with China. This proved to be a turning point: the KMT went on to be thrashed in municipal elections in late 2014. Some of the student leaders have formed their own party to contest the legislative election, joining 17 other groups and 556 candidates, who range from a heavy-metal front man to a former triad crime boss.

The last time Taiwan chose a DPP president, Chen Shui-bian, in 2000, cross-strait tensions escalated. Given China’s increasing assertiveness in the region under Mr Xi, things could be even more dangerous now. China has been piling pressure on Ms Tsai. Mr Xi says he wants a “final resolution” of differences over Taiwan, adding that this is not something to leave for the next generation. China is demanding that Ms Tsai approve the “1992 consensus”, a formula by which China and the KMT agreed there was only one China—but disagreed about what that meant in practice. Ms. Tsai has long said no such consensus exists, though when asked about it in a presidential debate, she called it “one option”.

Ms. Tsai is a very different figure from Mr. Chen, who delighted in provoking China (and was later jailed for corruption). She is a low-key, English-educated lawyer schooled in international trade rather than in the rhetoric of Taiwanese nationalism. She has gone out of her way to assure China and America, Taiwan’s guarantor, that she backs the status quo and will be cautious. Many of her proposals, such as that Taiwan should expand its soft power through non-governmental organizations, seem designed to be uncontroversial. If her party takes control of the legislature, that would remove a source of instability: conflict with lawmakers made Mr. Chen’s presidency even more unpredictable than it otherwise would have been.

Yet whatever Ms. Tsai’s intentions, a lot could go wrong. Taiwanese politics is famously raucous, and the DPP’s radicals seeking formal independence might yet cause problems. Mr. Xi, in turn, could come under pressure from military diehards arguing that China has been too patient. In one of the last foreign-policy vestiges of the “one China” idea, China and Taiwan have similar claims in the South China Sea, a nerve-racking part of the globe. If a new government in Taiwan starts tinkering with its stance on the sea, China might easily take offence. The election of an independence-leaning president comes at a dangerous moment.

JAPAN

Japan Economy, Housing Starts & Lumber Shipments

By Shawn Lawlor

Director, Canada Wood Japan

December 16, 2015

Japan Economic Update:

Japan edged its way out of recession as annualized GDP rose to 1.0% in the three months ending in September, following a contraction of 0.5% in the previous quarter. The increase was attributable to an 11% rise in capital spending. The Bank of Japan is maintaining the current rate of quantitative easing as BOJ Governor Kuroda expressed confidence that the economy is along a recovery path. Economists have commented however that it is likely that the LDP cabinet will table a further fiscal stimulus package late this year.

Meanwhile the LDP cabinet has been busy negotiating details of the next consumption tax increase in April 2017 with National Diet coalition member Komeito. The legislators are aiming to soften the impact of the tax increase to low income families by exempting certain food staple products from the 8% to 10% hike. Next year will also see changes on the corporate tax front. Beginning in fiscal 2016 corporate taxes will drop from 32.11 to 29.97% as the Japanese government aims for Japan to become more tax competitive globally.

Tokyo 2020 Olympic Stadium in Wood?

The selection for the National Stadium design for the Tokyo 2020 Olympics has been plagued by controversy. The initially approved proposal had an over the top futuristic design developed by British based Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid. This grandiose design fit in poorly with the surrounding neighborhood and ballooned to double the original budget of 130 billion yen. Prime Minister Abe then ordered the Japan Sports Council to shelve this plan and reopen a call for proposals for alternative designs.

It is now reported that two alternative designs have been submitted and both highlight wood in their construction. While the proposal proponents remain confidential, the initial responses to both proposals are positive due the selection of wooden materials, designs that fit better with the surrounding environment and are forecast to come below the 155 billion yen budget. One of the designs features extensive use of 72 massive wood pillars. The Japan Sports Council has yet to arrive upon a decision as to which design or general contractor company to award the project to. Canada Wood will monitor for opportunities for project involvement.

Jan 20th 2016, 17:42 by The Data Team Japanese housing starts fall below 900,000

Source: Fordaq

October housing starts data from the Japanese Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism show a continuing decline for the second consecutive month.

Japan’s October housing starts were the lowest since June this year and were down 2.5% from the same month last year.

As of October annualised housing starts stood at 862,000 down from the September forecast of 900,000. Looking ahead for the balance of the year prospects do not look good as orders placed with construction firms are well down (-25%) compared to the same period last year.

THE International Labour Organization’s latest “World Employment and Social Outlook” expects recent labour -market growth to slow in the coming years amid uncertain economic prospects. In the aftermath of the financial crisis in 2008-09 many countries suffered heavy job losses and soaring unemployment, especially in the West. The ILO thinks that unemployment will rise again in the coming years, and it is also anxious that the progress made in reducing the number of those who work but remain in poverty will stall. In the past two decades, earnings in emerging and developing countries have improved significantly. Those deemed to be poor (earning less than $5 per day at 2011 prices) have dropped from 78% of the world’s working population (excluding already-rich countries) in 1991 to an estimated 46% this year. The reduction in the “extremely poor” has been even more pronounced, with a fall from around a half to just 11.5%.

Even so, because of the increase in the working population, 1.2 billion people in emerging and developing countries are considered to be in relative poverty. That is only 200m fewer than in 1991. For those at the very bottom, earning less than $1.90 a day, the reduction is steeper, from 890m to 320m people. There are noticeable differences between regions. The biggest improvement has been in eastern Asia, where the number of those in poverty has fallen from 600m to 190m, while its workforce has grown by 155m. Other Asian regions have made good progress too. Latin America, though having a much smaller workforce, is also much improved. Sadly, though Africa has made some headway, a third of its working people are still extremely

Marginal House Price Improvements in China

January 25th 2016

On a month-on-month comparison, in November 2015, of the 70 medium and large-sized Chinese cities, new home prices have declined in 27, and remained unchanged in all others. For November 2015 the year-on-year change was positive.

Prices for second-hand residential buildings fell in a minority of the cities surveyed but rose as much as 2% in some others. The improvement in house prices came as a surprise to many but were greeted as a sign that there could be a recovery beginning in a sector whose performance mirrors the overall economy.

The housing market is a closely watch indicator for the Chinese economy as it accounts for around 15% of GDP and trends in housing impact many wood product manufacturers.

Fordaq News

Korean won’s fall seen to last with no remedy in sight

Korean Herald Published : 2016-01-25 16:05

The South Korean currency will likely keep falling against the U.S. dollar for some time and may drop as low as 1,300 won, with local authorities having little means or will to halt its slide, analysts here said Monday.

The local currency closed at 1,200.1 against the greenback Friday after dipping to 1,214.00 won two days earlier, the lowest level in over five years since 1,215.6 won posted on July 19, 2010.

The won’s depreciation is largely attributed to a slowdown in the global economy, but also to the recent U.S. rate hike that has apparently prompted a mass outflow of foreign capital from Asia’s fourth-largest economy.

As of Friday, foreign investors remained net sellers of South Korean shares for 35 consecutive sessions since Dec. 2, offloading some 6.2 trillion won ($5.18 billion) over the cited period and lowering their combined stake in the South Korean stock market to 31.02 percent of overall market capitalization, the lowest since August 2009.

The U.S. Federal Reserve is expected to continue raising its key rate following its first rate hike in nearly a decade last month while the European Central Bank is expected to continue its quantitative easing, a move that may help boost growth in Europe but further push up the value of the U.S. dollar in the global market at the same time.

“We expect an additional U.S. rate hike to take place in or after June, keeping the won-dollar rate at around the current level for now but pushing it down to a new low in the second half of the year,” said Lee Chang-mok, a researcher at NH Investment and Securities.

A recent report from NH Securities forecast the won-dollar exchange rate to reach 1,250 won against the dollar in the second half of the year.

Daishin Securities sees the rate reaching as low as 1,300 won due to uncertainties in the world’s second-largest economy.

“The market may come to be stabilized for now, but in the long run, the foreign currency market and oil prices will again witness two or three large fluctuations as they are greatly affected by uncertainties in China,” Daishin Securities researcher Cho Yoon-nam said.

Morgan Stanley, too, forecast the won-dollar exchange rate to find a new low this year at 1,300 won per dollar.

The problem is that local authorities may have little or no means to change the direction of flows of foreign capital, the market watchers said.

One of surest ways to prevent a capital outflow is to raise the country’s own interest rate, offering higher yields for foreign investment and thus making the market more attractive.

A more serious problem is that the local authorities may be reluctant to even take what little means available to stop the won’s depreciation, hoping it will help boost the country’s exports that suffered an on-year drop every single month last year.

The BOK has kept its key rate frozen at a record low 1.5 percent since June in an attempt to help bolster growth.

“There may be many elements that could trigger capital outflow and they include financial market fluctuations in emerging market countries, namely China, the speed of the United States’ monetary policy normalization and movements in global oil prices,” BOK Gov.

Lee Ju-yeol said on Jan. 14 when the BOK’s monetary policy board decided to again keep its policy rate steady in January.

“However, our economy is differentiated from other emerging market countries in terms of economic fundamentals and foreign exchange soundness, so I believe the country’s capital outflow will also be differentiated from those of other countries,”

Market watchers say that like in all other economic events, some stand to gain while others will suffer losses from the won’s devaluation.

They said many exporting companies may enjoy a sudden boost to shipments with large, export-dependent automakers expected to benefit the most from a further decline in the value of the local currency that will provide them with additional price competitiveness.

According to NH Securities, the country’s two leading automakers — Hyundai Motor Co. and its smaller affiliate Kia Motors Corp. — are expected to see each of their operating profits go up by nearly 1 trillion won if the average won-dollar exchange rate drops to 1,250 won per dollar this year.

The combined operating profit of 10 listed auto-related firms here, including Hyundai and Kia, is expected to spike 15.4 percent on-year to 16.58 trillion won, it said.

Such an effect, however, cannot last long, especially as the local carmakers continue to expand their overseas production, the analysts said.

“Japan had once sought to drive down the value of its local currency against the dollar and euro in an attempt to boost exports, but the move did not lead to an increase in its exports,”

the Korea Institute of Finance said in a recent report.

Others say the won’s drop is a double-edged sword whose damage could far outweigh benefits.